It happened two months ago running on a beautiful, sunny Saturday morning, March 13th. As more evidence of the unluckiness of the number 13, my route was a 13-mile “out-and-back.” I felt great and was running faster and faster on the mostly downhill “back” portion. I do not recall a specific bad event, just that the last half mile or so was uncomfortable and that I was limping a little afterwards then limping badly when I went for a longer walk a few hours later. I found when I tried to run during the next week that pain in the back of my right thigh – specifically, the mid-belly of my biceps femoris – prevented me from going anywhere near as far or as fast as I wanted to. I searched online for help with the diagnosis (probably a grade 1 tear) and recommended treatment then kept searching for additional discussions of treatment because I really, really did not like what they all said: “STOP RUNNING!”

Fortunately, I had recently begun developing a cross-training program of indoor (stationary) biking. At first, I completely replaced my runs with indoor biking. I found it much easier to have an alternative means of training than it would be to simply “not run” while waiting to heal. Later (well, not that much later, certainly not as much as those darn physiotherapist websites recommend), when I started running a little, I found biking consistently made my thigh feel much better.

It was sad, though. After a winter dealing with combinations of darkness, cold, wind, poor footing due to ice and snow, and then a “better” period featuring messy puddles of partly melted snow, I had been longing to experience the joy of spring running. Also, I need to ramp up my training so that the last miles of Grandma’s Marathon can possibly be more than simply a survival experience.

I soon transitioned to a phase of multiple weeks of uncomfortable runs (due to pain that gradually increased during each run), including some long ones, intermixed with indoor biking. I do not know if these runs slowed or helped my recovery. However, I am delighted that my latest seven runs have gone well (all in May, after those in the graphs below), including a hard group run (18 hilly miles) last Saturday, a 20 mile one today (!) and, in between, a couple of runs that included some higher speed intervals. I hate to risk jinxing things, but I think I may be back!

Running injuries are an immensely important topic: how and why they happen, what can be done to prevent them, how to treat them, how to think about them, and how they affect runners’ ability to persist with a practice of regular running, which is, apart from injuries, a lifestyle choice with phenomenal, multi-dimensional benefits. I cannot address any of these questions with expertise, but I do hope to write a future post about injuries that will include discussion of some published studies and commonly made recommendations relating to dynamic and static stretching, running drills, cross-training, strength training, and – for me, a particularly hard one to swallow – suggestions about running less (specifically, I hope to discuss the 2017 book by Bill Pierce and Scott Murr, Train Smart Run Forever). Today, though, I just want to describe my personal experience with running injuries over the last couple of years, with the important context of what sort of running I have been doing.

I am used to thinking about much of my running as “training” which is intended to be a cyclic process of STRESS -> RECOVERY -> ADAPTION -> (slightly more) STRESS -> RECOVERY -> ADAPTION -> and so on, where ideally the stress is enough to result in improvement or at least to prevent deconditioning. I define INJURY (or its cousin, overtraining) as what happens when the stress exceeds my ability to adapt, and classify my running injuries into three categories:

- Marathons, which are stresses of a magnitude that will probably always greatly exceed my ability to physically adapt so are type of “voluntary injury” that results for a while in a worse state of physical fitness – but possibly improvement in other dimensions of well-being.

- Disruptive injuries that significantly interrupt or degrade my running plans. I had three of these over the course of 32 months: a strained calf (soleus muscle) in September of 2019, three weeks before a planned marathon; a left hamstring injury last summer, about a month before the virtual version of my April marathon I signed up for when the in-person version was canceled by the pandemic; and then the right hamstring injury I mention above. Over these 32 months I recorded a little over 4,800 miles and around 720 hours of running, so my incidence rate of disruptive injuries was about 0.6 per thousand miles and about 0.4 per one hundred hours of running. It is useful to have a rate estimate like this because, when I am actively suffering from a running injury, I tend to feel so unlucky and sorry for myself that I forget how much I have been able to run without significant problems.

- Minor injuries that do not end up interfering with my running but may or may not be scary when they happen. For example, last October we had an early winter storm with lots of snow accumulation. I was running with a group on the pedestrian part of a freeway overpass but having a hard time keeping up due to hard, irregular snow, so I jumped down to what I though was clear pavement on the car part of the overpass. Yikes, it had a thin coat of ice! There was enough time between the start of my unrecoverable fall and pavement impact for the thought, “This could be really bad!” I tried to roll with my fall and ended up landing on and suffering blunt injury to the side of my chest that caused me discomfort for a few weeks (and initial worry that I might have fractured ribs) but did not stop me from running. As another example, I remember a run in March of 2020 at a time I was not about to touch the “Walk” button at a stoplight for fear of COVID-19 on the button (this was back when CNN was running a video with medical reporter Sanjay Gupta showing how to wipe down your groceries). When I sprinted hard to cross a busy road before some waiting cars got a green light, I felt a sharp pain in my upper, inner thigh. As I hobbled through the rest of my run, I was pleased I could diagnose it (adductor brevis strain/tear) but quite bummed by the prospect that I would not be able to run during the big COVID-19 lockdown (and poor me, what else was there to do?). However, the thing stopped bothering me after a few runs. Also in my category of “minor injuries” are things like finding one of my toenails has turned black (subungual hematoma) for unclear reasons or that my face has clearly gotten too much sun exposure (generally only a summer thing) because I really have not figured out a great strategy for preventing that.

I use a Garmin running watch, which uploads to an online Garmin database, at least when no cyber criminals have conducted a ransomware attack on Garmin (as happened in July of 2020). Using this online database, it is easy to export a file with a few metrics from all or any subset of your runs. I chose to explore 32 months of my recent history because I think I can remember the key details of all running injuries I suffered during that time.

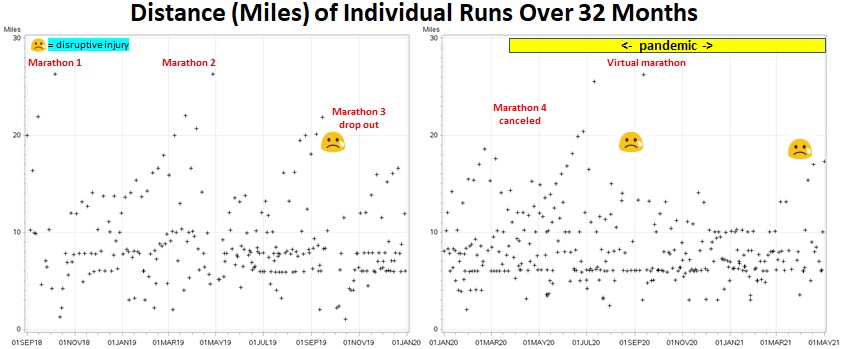

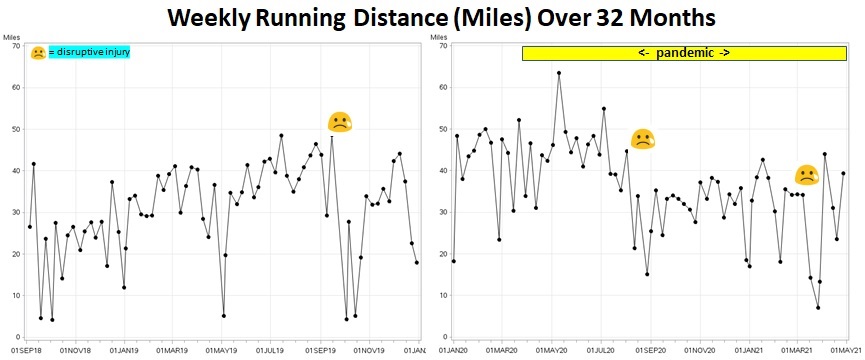

In the first pair of graphs (two consecutive 16-month time periods), the plus signs mark the date and distance of all my runs, the latter calculated by the Garmin watch by interacting with GPS satellites. You can see what looks like a parade of ants marching in line at 6, 8 and 10 miles (my most common distances), some time periods with progressively longer runs leading up to marathons, and three sad faces when I suffered those disruptive injuries. The next sets of graphs show these runs plotted as distance then as minutes per week.

The first injury (calf – soleus muscle) immediately followed a period with lots of long runs and relatively high weekly mileage. This is consistent with being an overuse injury, which is what people generally assume most distance running injuries are.

The next two injuries (left hamstring, right hamstring) are not so clearly associated with high running volume (in these graphs). Also, hamstring injuries are way more common, according to the expert discussions I have read, with shorter, faster running and sports like soccer and American football than they are with distance running. It is interesting, however, that quite a few of my running friends have had hamstring injuries from distance running. It may be more of an older runner thing.

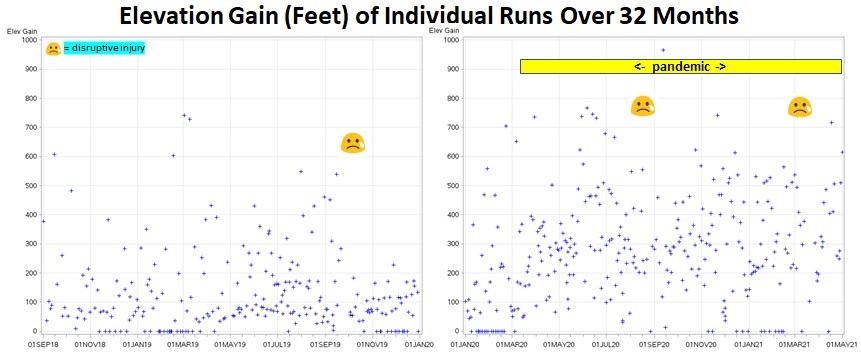

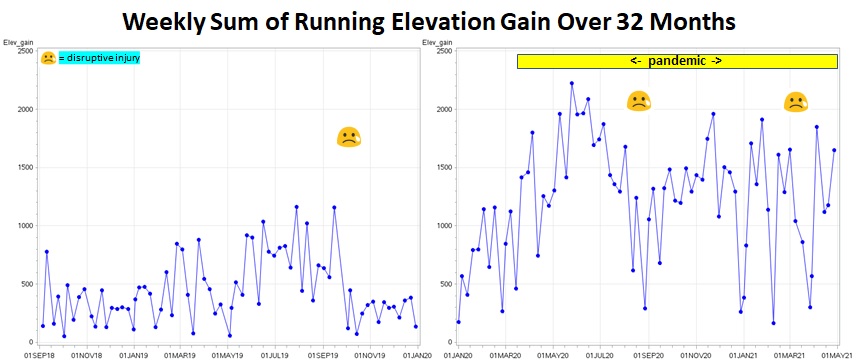

Part of the explanation for my hamstring injuries might be a change that occurred in my running during the pandemic that making these graphs showed was more dramatic than I had realized. I started running a lot more straight out the door of my home, which is in an area that is much hillier than where I mostly ran pre-pandemic. The next two sets of graphs show the elevation gain during individuals runs and cumulative elevation gain by week (my Garmin watch calculates elevation change from barometric pressure changes). You can see I had a huge increase in the amount of hill-climbing. (I should explain that the runs with elevation change of zero were indoor runs. I occasionally run on a treadmill, typically when there is a blizzard or a rainstorm happening. In the winter of 2019-20 I discovered that a nearby high school allowed people in the community to use their indoor track during certain hours, a better option than the treadmill but an option that went away with the pandemic. My Garmin watch estimates indoor run distance using its accelerometer/step-counter and usually is quite accurate.)

So how might hillier runs be part of the explanation? The hamstrings (semimembranosus and semitendinosus on the inside of the back of the thigh, biceps femoris on the outside – but for some reason it is only the biceps femoris that tends to be injured by running) are attached to the ischial tuberosity (sitting bone) and the calf (tibia and fibula, respectively). They are two-joint muscles that work both to flex the thigh and flex the leg (the “leg” is technically the part below the knee). The hamstrings play a key role is slowing down the leg in the last part of the swing phase of a leg during running (and a role in slowing down flexion at the hip, but the gluteus maximus is probably more important for that). This deceleration of the thigh and leg is so-called “eccentric contraction,” which is when a muscle is both contracting and lengthening, which is said to cause particularly high forces on the muscle – the cause of injuries. A lot of authors claim that the risk of hamstring injury is greatly increased when the quadriceps (knee extenders) become a lot stronger than the hamstrings (“ham-quad imbalance”) and that this is a common outcome of doing a lot of running, especially hill-running. My recent hamstring injury, of course, is probably additionally or alternatively explained by the fact that that I was exuberantly accelerating downhill on that ill-fated March 13th run.

There are a lot of ideas out there about plausible-sounding things runners can do to lower their risk of various types of injuries. However, there is apparently little objective evidence showing whether any of these do or do not work. One frequently mentioned exception is prevention of hamstring injuries in soccer players by adding the “Nordic hamstring lower” to their training. A published study described the incidence of hamstring injuries during four consecutive soccer seasons for 17 to 30 elite men’s soccer teams from Iceland and Norway. Baseline injury incidence was determined in the first two years and then injury incidence in the next two years was compared for teams that did versus those that did not use this eccentric hamstring training program. In the baseline period, the incidence of hamstring injuries was somewhat less than one per one thousand hours of training plus match play. During the two intervention seasons, the teams doing the Nordic lowers had a statistically significant 60% lower incidence of hamstring injuries compared with their baseline!

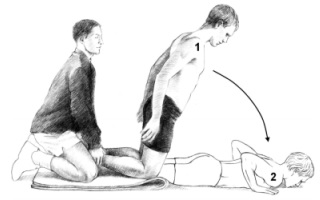

The figure below shows a Nordic lower. The players were told: “This is a partner exercise, in which your partner stabilizes your legs. The goal is to hold as long as possible, to achieve maximum loading of the hamstrings during the eccentric stage. Lean forward in a smooth movement, keep your back and hips extended, and work at resisting the forward fall with your hamstring muscles as long as possible until you land on your hands. Touch down with your hands, go all the way down so that your chest touches the ground and forcefully push off into a kneeling position with minimal concentric load on the hamstring. Load is increased by attempting to withstand the forward fall longer. When you can withstand the whole range of motion for 12 repetitions, increase load by adding speed to the starting phase of the motion. Initial speed and load can also be increased further by having someone push you at the back of your shoulders.”

I tried doing Nordic lowers by wedging my feet under the living room couch. Unfortunately, I found that I could not “lean forward in smooth movement” far at all before falling on my hands. My big idea, therefore, was that maybe the training machine known as the Glute-Ham Developer (GHD) would be easier and better (see YouTube video, below). One of my “running family” members, Jamie K., is a former star college soccer player (star high school player and probably star from much earlier). She confirmed that elite soccer players today do use this exercise and that they are easier on a GHD. My new plan is to start a GHD Nordic lower program shortly after Grandma’s Marathon!

Leave a comment