Was it too greedy to plan a second marathon just two months after my last one? All was going well until it wasn’t, two weeks before race day, after a 15-mile run prescribed by my coach for the end of my first week of “tapering” for the race. I did not get to participate in the race, but now I am having the opportunity to learn more about tibialis posterior tendinopathy and (hopefully) how to recover from it and prevent it from recurring.

- The Tibialis Posterior Muscle & Tendon

- Movements with which Victims of TP Tendinopathy (Like Me) have Problems.

- Movements of the Ankle and Foot Involving TP Muscle.

- Insights into Movements of Ankle & Foot from a Running Gait Analysis.

- “He who treats himself has a fool for a patient.”

The Tibialis Posterior Muscle & Tendon

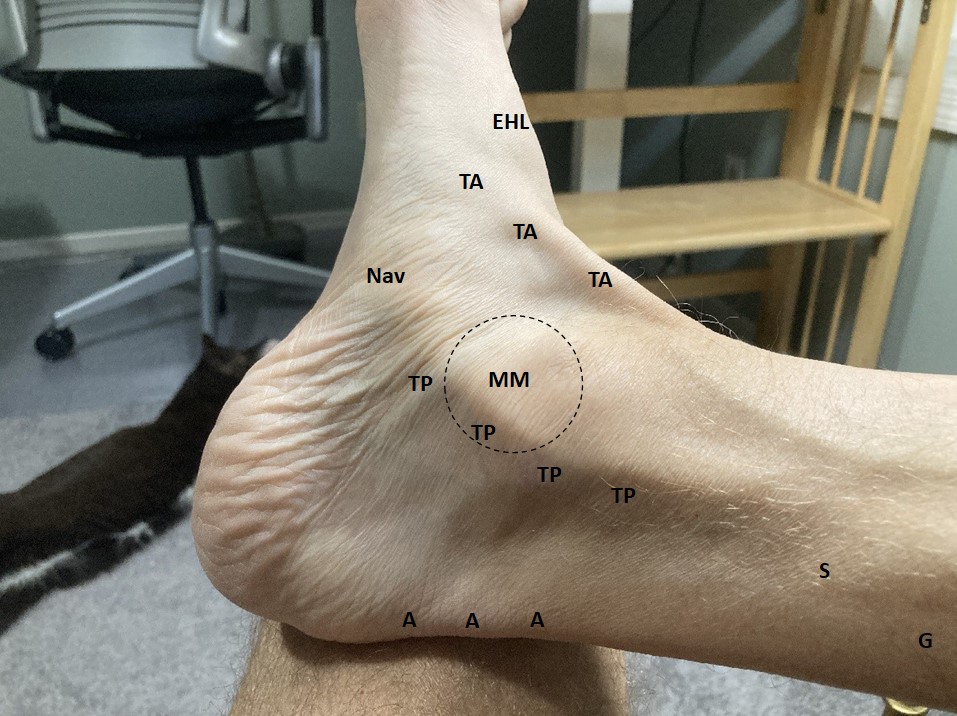

The tibialis posterior (TP) muscle is the deepest muscle in the posterior compartment of the leg. Most of it is very hard to palpate. The tendon of the TP muscle, however, runs close to the skin surface and is easy to see on me. It emerges in front of the soleus muscle then loops down and around the medial malleolus (big protuberance of the tibia on the inside of the ankle joint) en route to the instep of the foot, where it can be seen/felt attaching to the navicular tuberosity (prominent bump on the medial side of the foot at the top of the arch).

In the picture of my lower leg and foot (Figure 1), it was exactly along the path I have marked TP that I felt pain after that 15-mile run, which led me to the probable diagnosis of TP tendinopathy.

Movements with which Victims of TP Tendinopathy (Like Me) have Problems.

This diagnosis of TP tendinopathy was further supported by observing I now had pain and weakness with movements in which the TP muscle plays a role. Specifically:

- Raising/lowering onto/from my toes on the injured side.

- Early post-injury I could only manage a few, rather wimpy single leg heel raises. It was painful and weak both pushing up onto my forefoot and going back down. Ten weeks out I am finally getting better at single leg heel raises. This morning I could do 25! My non-injured side, of course, has no problem doing way more than that.

- Pain and an unsound feeling walking downstairs.

- Balancing on one leg on the injured side. I am unsteady and tend to tip over.

- Rotating my foot inward on the injured side (especially against resistance, e.g., closing a low kitchen drawer with my foot).

- Running. Initially the injured side was extremely painful when I attempted to run. I am now able to run every other day and am very slowly ramping up my distance. The most convenient (and safest since most of my outdoor running options are extremely icy) place I have found to run is an indoor track with very sharp corners (see Figure 2). The only discomfort I experience is when going around these corners counterclockwise (injured foot on the inside at the turns), which requires rotating the rest of the body in at the foot (same motion as rotating the foot out with the rest of the body fixed).

Movements of the Ankle and Foot Involving TP Muscle.

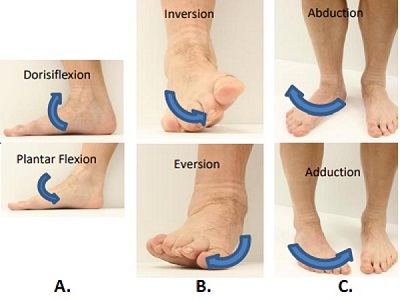

There are three “fundamental movements” of the ankle and foot. Figure 3 shows the X, Y, and Z axes used to measure these in three-dimensional running gait analysis. I took the Figure 4 images from the report of a running gait analysis done on me in April (from their key to the movements described – these are not my feet).

- Dorsiflexion/plantarflexion occurs in the X-Y plane (sagittal plane).

- Plantarflexion is movement of the foot downward along the Y-axis, hinging at the true ankle joint between the tibia and the highest tarsal bone, the talus (“talocrural joint” – crura is derived from the Latin word for leg). Dorsiflexion is hinging upward along the Y-axis.

- The TP muscle plantarflexes the foot to push off from the ground when running or walking (“concentric contraction” – the TP shortens during contraction). The TP muscle also contracts to control loading as the ankle dorsiflexes during the first place of the stance phase of running (“eccentric contraction” – the TP lengthens during contraction).

- The soleus and gastrocnemius muscles are much more powerful plantarflexors. (The soleus, famous for its high percentage of slow-twitch muscles, does a large fraction of the work in distance running.)

- Inversion/eversion occurs in the Y-Z plane (frontal plane).

- Inversion is movement of the foot upward along the Y-axis, turning the bottom of the foot inward by raising the inner (medial) arch of the foot. This motion occurs at the so-called “lower ankle joint” between the talus and calcaneus (“subtalar joint”). Eversion is movement the other direction, turning the bottom of the foot outward.

- The TP muscle inverts the foot by concentric contraction and controls eversion by eccentric contraction. During the running gait cycle, the foot is inverted at initial contact with the ground (medial arch is high and off the ground) then the foot everts (rolls inward), flattening as load is absorbed. Finally, the foot rolls back the other direction (inverts) during the push-off from the ground. (The gait analysis graphs below help with understanding these movements.)

- The tibialis anterior muscle works together with the TP during inversion/eversion – also causing inversion through concentric contraction and controlling eversion through eccentric contraction. These two muscles play an important role in maintaining balance when standing by raising the medial arch of the foot to counteract leaning.

- Abduction/adduction occurs in X-Z plane (transverse plane).

- Abduction is turning the foot out from the midline on the Z-axis. Adduction is movement of the foot towards to midline (e.g., from an out-turned position). This motion is also at the between the talus and calcaneus (“subtalar joint”).

- The TP muscle adducts the foot by concentric contraction. During the running gait cycle, the foot is usually out-turned (abducted) at initial contact with the ground, becomes more progressively more out-turned between initial contact and midstance, then returns to the initial contact position at toe-off. People vary a lot in how “duck-footed” their gait is!

Supination and pronation are complex combinations of these fundamental movements:

- Supination is a combined movement of inversion, adduction, and plantarflexion.

- Pronation is a combined movement of eversion, abduction, and dorsiflexion.

- Supination and pronation involve the subtalar joint and the “transverse tarsal joint,” which is comprised of joints between the talus and the navicular bone and the calcaneus and the cuboid bone (i.e., between the hindfoot and midfoot). These motions occur in a standard pattern while running that can be finely (or radically) modified to adapt to running on irregular surfaces.

Insights into Movements of Ankle & Foot from a Running Gait Analysis.

I had a gait analysis performed about ten months ago. My running gait has some very weird features I wanted to understand better in hopes of getting useful insights into injuries I have had or may be at increased risk for and, possibly, suggestions about how I might lower my risk of future injuries. This seems like good time for me to review the ankle-foot results from this analysis because I am trying to piece together a program that will not only result in recovery from this injury but, hopefully, improve other aspects of my running and other activities, give me a more resilient ankle and foot, etc.

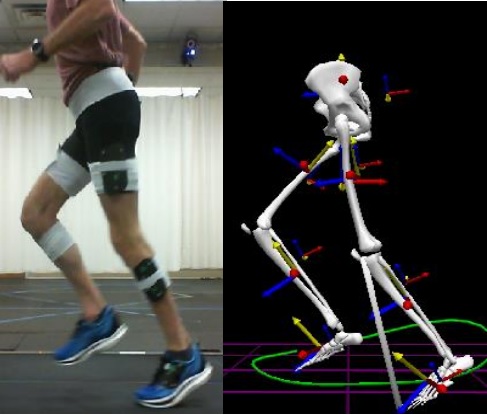

The gait analysis lab that studied me has a treadmill set up in a pit so that its running surface is even with the floor. The treadmill has a force plate, which is used to measure forces exerted on the runner during the gait cycle. They attach lots of infrared light-reflecting “markers” to landmarks on the runner’s pelvis, thighs, legs, and feet. These markers are tracked in a very carefully calibrated three-dimensional space by 12 detectors arrayed around the treadmill, using commercial software that creates a model of the runner’s pelvis, hips, thighs, knees, legs, ankles, and feet (see Figure 5). The lab also has video cameras that record the runner’s motion.

The output of this analysis was a report with graphs of my joint motions (kinematics) and forces (kinetics) during the running cycle, along with a terse textual summary comparing me with the results from an unspecified population of runners studied using the same protocol (their reference ranges). They also gave me short video files showing a side view and a rear view of me running with synchronized graphs tracking my joint angles. I would have loved a lot more explanation of the whole process and discussion of the findings, of course.

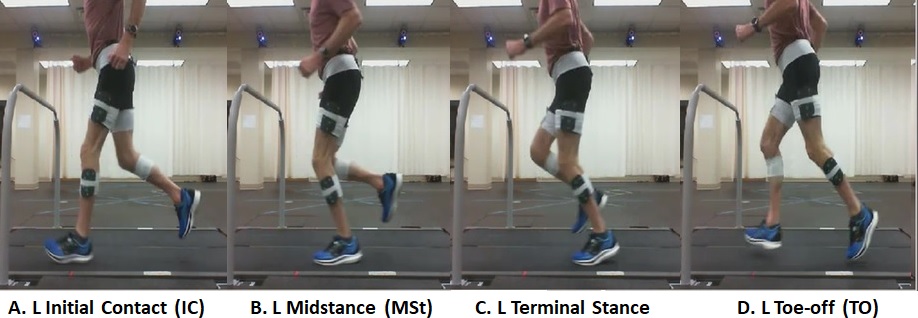

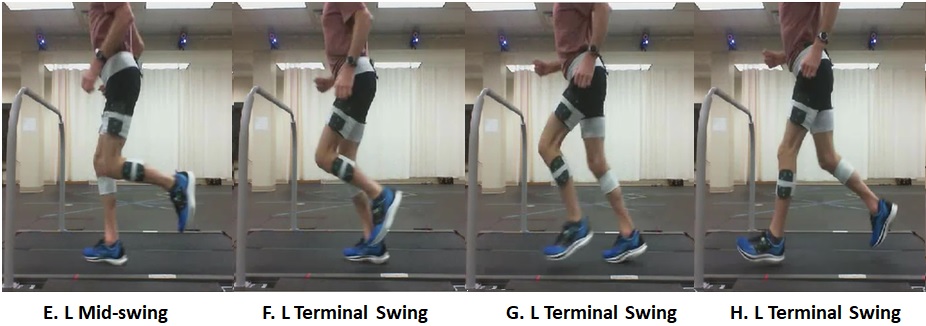

In the running gait cycle (see Figure 6) each side (left and right) progresses through alternating periods when the foot on the ground (stance phase) or swinging back then forward to the next step (swing phase or “float”). Only one foot is on the ground at any one time and there is a period (“double float”) when both are off the ground.

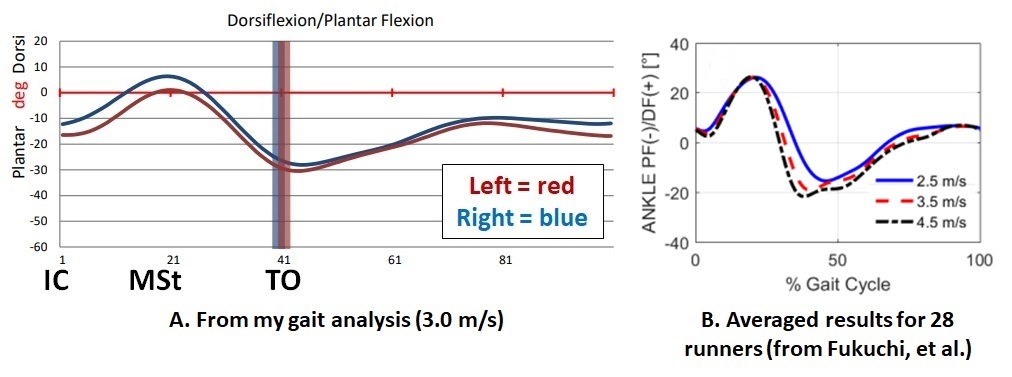

Gait Analysis Results: Ankle Dorsiflexion/Plantarflexion

The next three sections show my gait analysis report graphs of ankle-foot kinematics alongside similar graphs from the scientific paper cited above, which show averaged results from gait analysis of 28 “regular runners” at three different running speeds.

Figures 7A and 7B (sagittal plane) show the pattern of dorsiflexion increasing from initial contact (IC) to a maximum at mid-stance (MSt) when the “ground reaction force” (GRF) from impacting the ground is at a maximum. (GRF is the force passing vertically from the ground into the body, equal and opposite to the force of the foot hitting the ground. Another section in my report shows that my vertical GRF hit a maximum of 2.25 Newtons per kilogram at MSt, which translates to about 2.25 times my bodyweight of 160 pounds – a peak of 360 pounds in force that must be absorbed with each running step!)

From midstance to toe-off (TO) the foot plantarflexes to push off the ground.

To increase speed, a runner can increase cadence and/or increase stride length by plantarflexing more powerfully. Figure 7B shows, on average in the study sample, with increased speed from 2.5 to 4.5 meters/sec, the ankle plantarflexes further and a smaller fraction of the gait cycle is spent in stance phase (more float time).

My results were summarized in the report as “low normal plantarflexion.” I wonder if this was just because of my running speed. Did they set the treadmill on an “old guy” speed then compare with a reference range derived from mostly from younger people running faster? Of course, it seems possible that older runners (or at least I) may tend to run a given speed at a higher cadence with less ankle movement due to weaker calf muscles and/or less ankle flexibility. It would be nice if my gait analysis included more than one speed.

My report noted that their system showed 11.8 degrees of plantarflexion when I was standing and that often (in other gait labs) this “is reported as zero degrees of flexion and thus the curves could be moved 11.8 degrees towards dorsiflexion.” The running shoes I was wearing have a “heel drop” of 8 mm; perhaps this is the reason from my standing plantarflexion?

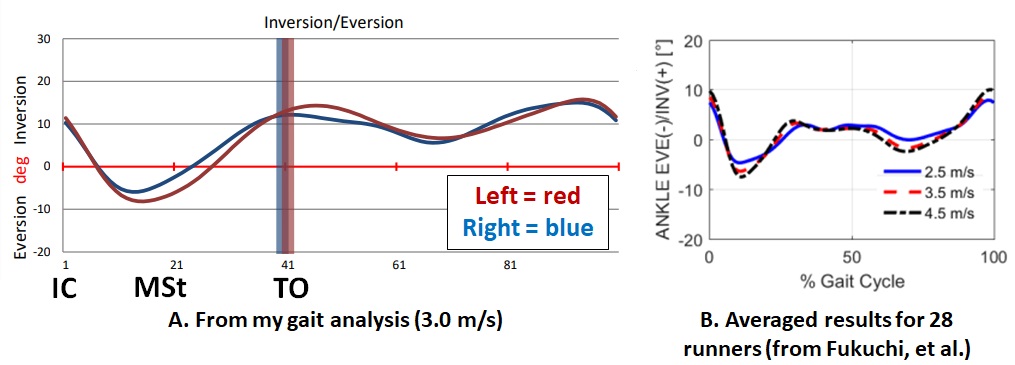

Gait Analysis Results: Ankle Inversion/Eversion

Figures 8A and 8B (frontal plane) show the foot inverted IC then rolling inward to maximal eversion at MSt before rolling back (inverting) before TO. For great slow motion views of this movement see this video of Eliud Kipchoge and his pacers running: eliud kipchoge slow motion video – Google Search .

Figure 8B shows, on average in the study sample, with increased speed the foot everts farther at mid-stance.

My results were simply summarized as “High normal inversion at IC and last one-third of swing phase bilaterally.”

Since I am now using TrainingPeaks software to make detailed records of all my runs (see my previous post), I have some prospectively acquired information relating to training errors that may have contributed to my TP injury. I opened this blog post by saying, “All was going well until it wasn’t, two weeks before race day, after a 15-mile run.” However, reviewing my records, I recall that I had clues that all was not going perfectly:

- On the preceding Sunday, I had completed the “peak week” training plan my online coach prescribed. This was 60.5 miles for the week, the same as before my October 1st marathon but with a faster ramp up in the weeks leading up to this.

- I ran a 20-mile rolling hills route as my Saturday long run and noted feeling “flat” in the last miles of this.

- After that Saturday, the first very cold weather of the season moved into our area, so I ran my assigned Sunday run (nine miles) on a treadmill. I noted that it felt uncomfortable (in addition to being extremely boring, which is why I have done very little treadmill running).

- My next assigned run was an 8-mile “progression run,” increasing pace every mile to finish the last mile at a pace that is quite fast for me. A lot of snow had accumulated outside so I opted to go to (rather old!) high school indoor track open to the public before the start of their school day. I had never run on this track before. I completed the assigned run but noted that the track surface seemed very hard. I felt like my feet were taking a beating. Looking back, I suspect the track surface is not unusually hard (though I am not going back to see!) but that I was already well along to hammering my feet and ankles towards injury.

- That sad 15-mile run that did me in was on a cold day with wicked wind gusts (wind chill about 5 degrees F). I chose to run around and around a nearby park that has a lot of protection from the wind. This was not a happy run. I noted that I felt “flat-footed” throughout the run!

My hypothesis is that my TP tendon injury was the result of progressing up to a failure point (for me and my training history) in peak week, then finishing off the damage with runs that probably had excessive eversion (pronation). I will try to approach my next pre-marathon build-up and taper in a gentler way if I am lucky enough to get to this stage again!

Gait Analysis Results: Ankle Abduction/Adduction

Figures 9A and 9B (transverse plane) both show the pattern of the foot abducting (turning out) from IC to MSt, then adducting (turning back in) from MSt to TO.

Comparison between my results and those in the published study is complicated by use of a different vertical axis by the two labs – and the fact that my gait is so much different. My graph shows abduction as movement up the vertical axis vs. down the vertical axis in the research study’s lab. Also, my graph shows MUCH higher abduction throughout the gait cycle.

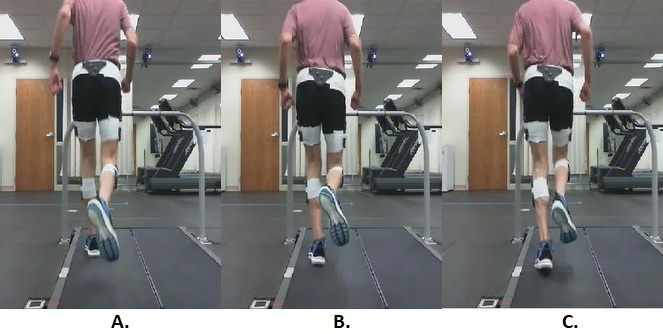

My results were summarized as: “High normal abduction throughout the cycle bilaterally, more so on the right. Increased max right abduction at mid-swing.” Not shown in this blog post are my knee and hip gait analysis results, both of which show marked external rotation (more so on the right). I believe the ankle-foot abduction may mostly be due to these external rotations. This whole set of abnormal movements is partly what I had a gait analysis to better understand, and I still need help with understanding what is going on.

When I run, walk, or stand my feet turn-out a lot (I’m “duck-footed”). I think I have been this way for my whole life. Considerable out-toeing seems to be fairly common (even among good runners), based on my own observations of people running and walking. When I am walking in the winter, I often get good opportunities to look at others’ footprints. Most people walk with straight-ahead (parallel) feet, but I often see footprints with turned out toes, sometimes more than my own. (I repeatedly see footprints in a nearby park that have are exactly the same size and angle as mine but with different tread, so I know it was not me. My “footprint double!”)

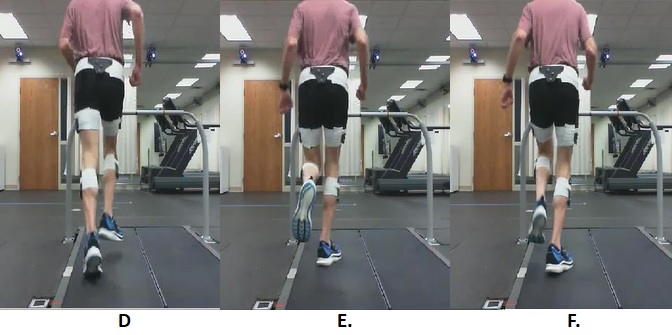

Figure 10 shows a bit of what I am talking about. You can see that both of my feet turn out. On my right side, my heel flicks toward the left side, crossing the midline. My right thigh and leg circle out and back on the way from swing reversal to right IC; much of the turning out appears to me to be due to external rotation of the thigh and leg. It is my left side, though, that had the TP injury.

“He who treats himself has a fool for a patient.”

A hard feature of running injuries for me is that I often cannot tell how bad something is hurt or whether it is getting better or getting worse without running. I tend to take a lot of “test runs” after realizing something has gone wrong. I have frequently had “niggles” that got better quickly and believe that continuing running may have been helpful in fixing the problem or at least not bad for whatever was wrong while being “good” for the larger me because I like running. However, when things get worse or stay bad for a long time, I feel foolish and guilty. Would I have recovered sooner if I were not so obsessed with running?

It has also been hard for me to figure out how and from whom I might seek professional help with running injuries. I know I could often benefit from seeing a medical professional with training (and interest) in running injuries. However, I worry about the costs and whether the person I might see is interested and good at diagnosing and managing a runner like me.

I finally did identify a physical therapist who specializes in running injuries and have seen him twice. (A PT to look at my TP!) The first visit, last week, was mostly history and physical exam, from which he concluded the TP tendinopathy was probably the correct diagnosis. He prescribed a couple of daily exercises (eccentric heel lowers on a stair step and ankle inversion/adduction resisted with a stretchy band), both of which seem to be helping. Today he did some manual therapy, stroking along the course of my TP tendon with a metal tool, then his fingers, then manually everting/abducting my ankle while I resisted and resisting my TP contraction to create the opposite movements. I have a second follow-up visit in a few weeks.

I am hopeful and excited that he can help guide me to a sensible path back to my previous level of running health and beyond to a more resilient body, better balance, etc.!

Leave a comment