My preceding post explored the question of how much endurance exercise is ENOUGH to get all its benefits. This post begins my exploration of medical concerns about damage to the heart from too much endurance exercise. The most frequently discussed concerns are increased-for-age coronary artery atherosclerosis (AS) and the heart rhythm disorder atrial fibrillation (AFib) (see Figure 1).

About three years ago, during my annual preventive care visit my doctor suggested that I should get a CT (computed tomography) scan to determine my CAC score, a measure of the amount of AS in my coronary arteries, to help decide whether I should start taking a statin despite having a fairly low LDL-cholesterol (84 mg/dL at that time) and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD) “risk enhancers.” He was following current clinical guidelines (see below) for statin decision-making for a patient (like me) with (1) low “traditional risk factors” for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) other than being male and being in my mid-60s (which are very big, unmodifiable risk factors!) and (2) concern about possible adverse drug effects from statins.

I was very unhappy to learn that I had a high CAC score.

In this post I will discuss:

- Does the long-term amount and intensity of endurance exercise typical of what many unremarkable recreational runners (like me) attempt to achieve, increase the amount of atherosclerosis in their coronary arteries? Was running the cause of my high CAC score?

- If yes, does it increase their risk for the bad outcomes of coronary artery disease (CAD), such as myocardial infarction or sudden cardiac death?

- Is there evidence that endurance athletes with high CAC scores would be wise to cut way back on their endurance exercise?

(In a future post, I would like to discuss AFib in endurance athletes.)

- 1.Background Info About Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease

- 2. Measuring the Amount of Coronary Atherosclerosis Using Computed Tomography (CT)

- 3.The Studies that Found Evidence that High Volume Endurance Exercise is Associated with Advanced-for-Age Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis

- (3a) A study of 108 male marathon runners & 216 controls in Germany (Möhlenkamp, et al., 2008)

- (3b) A study of 50 male marathon runners & 23 controls in the U.S. (Schwartz, et al., 2014; Roberts, et al., 2017)

- (3c) A study of 152 male + female endurance athletes & 92 controls in the U.K. (Merghani, et al., 2017)

- (3d) A study of 318 “middle-aged sportsmen” in the Netherlands (Braber, et al., 2016 and Aerngevaeren, et al., 2017)

- (3e) A study of 191 lifelong male endurance athletes, 191 late onset male endurance athletes, and 176 male non-athletes in Belgium (De Bosscher, et al., 2023)

- (3f) A study of 21,758 male patients seen at a preventive medicine clinic in the U.S. (DeFina, et al., 2019)

- 4. Why Are Endurance Athletes More Likely to Have High CAC Scores than Non-Endurance Athletes with the Same Level of Traditional CAD Risk Factors? Could Lipoprotein(a) Level Be a Key Missing Variable in the Studies?

- 5. Risk of the Bad Outcomes of CAD in Endurance Athletes with Increased-for-Age Coronary Atherosclerosis

- 6. My Current Thoughts About Endurance Exercise & Risk from Coronary Artery Disease

- References

Before describing the relevant research studies of endurance athletes, I will try to provide some background information about CAD and computed tomography (CT) imaging of the coronary arteries. (Coronary CT is the technology used in the studies of endurance athletes that have shown increased coronary atherosclerosis.)

Note: These sections are just an attempt to write a simple, concise description based on my current understanding. Atherosclerosis and its consequences are enormously important, complex, and evolving topics, way beyond my ability to accurately summarize in a blog post.

1.Background Info About Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease

(1a) Atherosclerotic Plaques

The walls of the coronary arteries have three layers surrounding the central lumen through which blood flows. Moving from the inside to the outside these are: (1) the intima, which consists of an innermost, single cell thick lining of endothelial cells called “the endothelium” with an underlying “basal lamina” (mostly collagen) and usually (in the absence of atherosclerosis) a very thin, deeper layer of loose connective tissue; (2) the media, which consists mostly of smooth muscle cells, whose contraction or relaxation changes the diameter of the lumen; and (3) the adventitia, an outer layer of connective tissue.

Atherosclerosis is thought to be initiated by injury to endothelium by factors such as hypertension (high blood pressure), hyperlipidemia (specifically high blood cholesterol), toxins (for example, from cigarette smoking), and chronic inflammation (many potential causes). Genetic risk factors can play a VERY important role and may result in a family history of early heart disease.

This injury causes dysfunction of the endothelium including:

- Increased permeability of the endothelium to the cholesterol-carrying LDL particles (Low Density Lipoprotein particles, the main transporter of cholesterol) in the blood and accumulation of LDL particles in the loose connective tissue of the intima, and

- Adhesion of monocytes (a type of white blood cells) and their emigration (movement) across the endothelium into the loose connective tissue of the intima where they transform into activated macrophages.

An atherosclerotic plaque subsequently develops in the intima:

- Macrophages (which are the “professional janitors” of the body) engulf LDL-cholesterol particles that have leaked into the intima and become lipid-laden “foam cells.” Foam cells and dead foam cells accumulate as the fatty “core” of a plaque.

- Various factors released by the macrophages (and other cells) stimulate smooth muscle cells (SMCs) to migrate from the media into the intima and to begin expressing different genes. These (now) intimal SMCs proliferate and synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM, consisting of collagen, etc.) that strengthens the “cap” of the plaque.

- Variable numbers of T-lymphocytes infiltrate the plaque as part of a chronic inflammatory process.

Plaques may have only a thin cap or may have a thick cap with lots of collagen. The ECM in the cap and necrotic debris in the core of the plaque may become calcified (accumulate calcium crystals). A thick cap and dense calcification of the ECM are features associated with stable plaques (less likely to rupture). A thin cap is a feature associated with unstable plaques (more likely to rupture).

Since statins are among the most prescribed drugs in the U.S., it seems important to comment on the effects of statin therapy on atherosclerosis and plaque morphology.

- Statins lower LDL-cholesterol levels in the blood by inhibiting cholesterol production by the liver and, indirectly (by feedback regulation), by causing liver cells to increase (upregulate) their LDL receptors and removal of LDL-cholesterol from the blood.

- Statins also have several other important effects that reduce progression of atherosclerosis and/or its bad outcomes by decreasing the endothelial cell dysfunction and chronic inflammation associated with atherosclerotic plaques.

- Statin treatment causes reduction in the cholesterol content of plaques, a significant increase in their calcification, and favors development of more stable plaques. (Reference #2.)

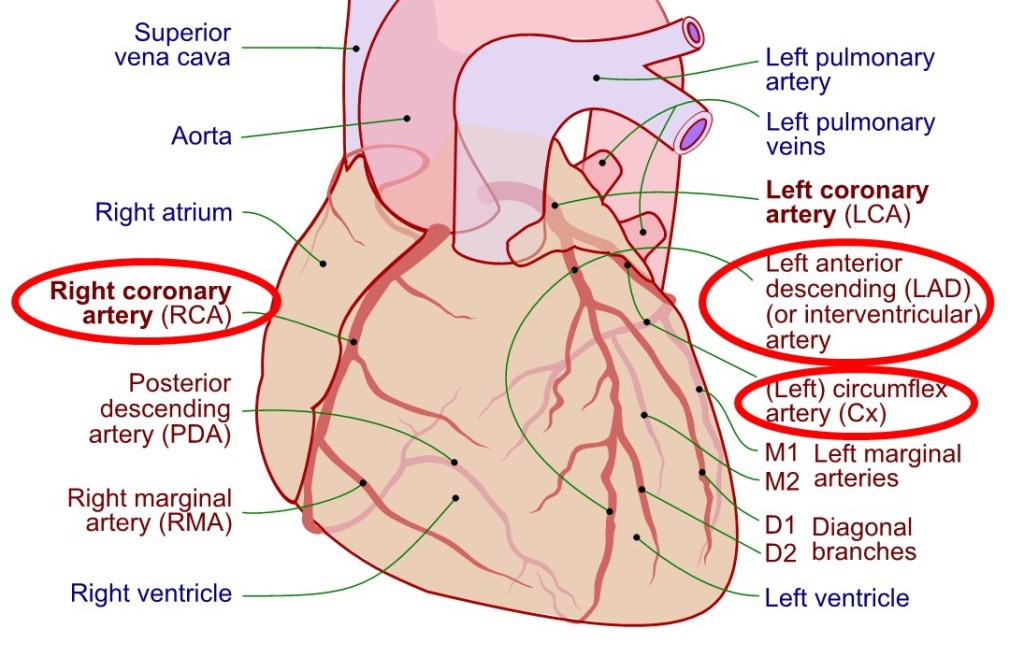

Two coronary arteries (right and left) originate from the first part of the aorta (just downstream from the aortic valve), travel on the outer surface of the heart, and branch into smaller and smaller arteries that eventually plunge into the heart muscle and terminate in capillaries where oxygen, nutrients, etc. are delivered to, and carbon dioxide, waste materials, etc. are removed from the heart muscle cells (see Figure 2).

There is evidence that the development of atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary arteries typically starts before early adulthood. (For example, several autopsy studies of young American soldiers killed in combat found a high prevalence of atherosclerosis.) The number and size of plaques increases throughout the following decades.

(1b) Consequences of Coronary Atherosclerosis

Plaques can result in myocardial (heart muscle) ischemia – insufficient blood flow to match the oxygen demands of the heart muscle – by two different mechanisms:

- Chronic, progressive stenosis (narrowing) of one or more coronary artery branch from the slow enlargement of a plaque. A narrowing of >= 70-75% of the lumen diameter is said to be a “critical stenosis” likely to exceed the capacity of the artery to dilate enough to meet even a moderate increase in demand by the myocardium.

- “Acute plaque changes.” Sudden rupture of the plaque or erosion of its overlying endothelium can lead to rapid complete or partial occlusion of the artery by formation of a thrombus (a clot of activated platelets, fibrin, and entrapped red blood cells). Thrombus formation (thrombosis) is triggered when platelets in the blood are stimulated by contact with the ECM of the intima or the contents of the plaque core. Most coronary artery occlusions are now thought to result from acute plague changes in plaques that did not cause a critical stenosis prior to the acute changes.

Common manifestations of myocardial ischemia include:

- Asymptomatic ischemia detected during a cardiac stress test (for example, electrocardiogram [ECG] changes observed when a patient exercises on a treadmill at progressively increasing speed plus incline). This may be caused by one or more chronic critical stenoses.

- Stable (exertional) angina, which refers to recurrent episodes of transient (lasting 15 seconds to 15 minutes) chest pain or other symptoms during increased PA (and/or other physiologic or psychologic stress) when increased oxygen demand by the heart muscle cannot be satisfied by a chronically narrowed artery.

- Unstable angina, which refers to more prolonged (> 15 minutes), intermittently worsening and/or severe chest pain or other symptoms resulting from acute plaque changes with resulting thrombosis that has not (yet) caused complete obstruction. This is commonly the precursor of a “heart attack,” during which rapid intervention is imperative – ideally summoning paramedics and getting rapid transport to a center capable of coronary angioplasty/stenting. (For a recent first-person account by a 66-year-old journalist who survived, see I didn’t know I was having a heart attack, and it nearly killed me. – The Washington Post. For a recent column by another journalist, who lost her 61-year-old friend and running partner who had nausea and fatigue after a bike ride but did not recognize it as an acute coronary syndrome, see Heart health, women and the limits of exercise to prevent heart disease – The Washington Post.)

- Myocardial infarction (MI). This most often results when acute plaque changes trigger complete obstruction by a thrombus, which leads quickly (in 20 to 40 minutes) to death of cardiac muscle cells supplied by the artery. The outcomes of an MI depend on the amount and location of cardiac muscle loss. Small MIs may be asymptomatic (“silent MI”) and only discovered during subsequent screening. Other MIs may cause death within hours to weeks or be physically or psychologically disabling and/or lead to a long downward spiral of heart failure.

- The potentially fatal arrythmia called ventricular fibrillation can result in cardiac arrest (loss of effective heart contractions) and sudden cardiac death if the heart is not re-started by resuscitation efforts such as use of an automated external defibrillator (AED). Ventricular fibrillation may be caused by marked ischemia in the ventricles due to EITHER: (1) chronic stenosis, when marked ischemia in the ventricles results, for example, during very intense PA or (2) acute plaque changes triggering thrombotic occlusion of an artery.

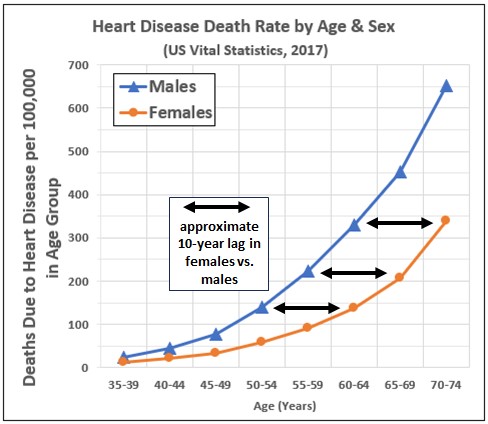

In the latest publicly available death certificate data, heart disease — overwhelmingly resulting from CAD — was the number one or number two top cause of death in each five-year age group of males in the U.S. older than 40 and each five-year group of females older than 50. (The other top cause of death was cancer. In the older age groups COVID-19 rose to a distant number three position in 2020.)

- The death rate from heart disease among females aged 50 to 74 consistently lags that of males by about ten years (see Figure 3).

- The death rate from heart disease among females 75 and older begins to catch up with that of males (not shown).

2. Measuring the Amount of Coronary Atherosclerosis Using Computed Tomography (CT)

(2a) Coronary CT and the Coronary Artery Calcification (CAC) Score

Coronary CT is a procedure in which a beam of X-rays is aimed at the heart to very rapidly acquire signals that are then computer-processed to generate thin cross-sectional images (“slices”). The “very rapidly” part is important because it has to be fast to get non-blurry images and because x-ray radiation has adverse effects, including increased cancer risk, so every effort is made to minimize exposure.

Coronary CT can be performed with or without intravenous injection of contrast material (radio-opaque chemical dye).

All of the six published studies I have found of the association of endurance exercise with coronary atherosclerosis, used a coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan, which does not require contrast material.

- This type of CT determines the size, locations, and density of calcified plaques. It cannot detect non-calcified plaques or determine the amount of artery narrowing associated with any plaque.

- A standardized and highly reproducible coronary artery calcium score (CAC score, in Agatston units) is calculated by multiplying the area of each calcification on the CT slices times its density score (1, 2, 3, or 4), then summing these for all calcifications.

Four of the athlete studies also used a coronary CT angiogram (CCTA), which does require contrast material.

- In a CCTA, the contrast material makes it possible to see all the plaques. A radiologist can visually categorize plaques by their composition (e.g., calcified, non-calcified, or “mixed”) and other features. Also, the amount of narrowing associated with each plaque can be measured.

- The use of contrast material carries the risk of an adverse reaction, such as coronary artery vasospasm. Also, performing a CCTA after a CAC scan exposes a patient (or research subject) to at least twice as much radiation.

The CAC score has been extensively studied as a screening test to detect and quantify “subclinical” (not symptomatic) atherosclerosis and to refine prediction of a patient’s cardiovascular outcomes.

(2b) Association Between CAC Scores and Long-term Health Outcomes

One of the most helpful research studies of CAC scores is the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).

Between 2000 and 2002, this study selected and obtained baseline CAC scores for a representative sample of 6,722 men and women in the U.S. from four racial or ethnic groups (white, black, Hispanic, and Chinese), none of whom had clinical cardiovascular disease at study entry. (Reference #3)

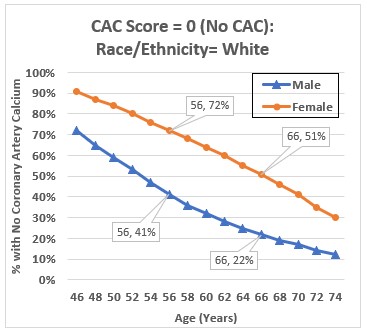

Figure 4 plots the percentage of white MESA study participants by sex and age who had a CAC score of zero at the start of the study. I obtained these numbers by plugging race/ethnicity, sex, and age into the reference values calculator on the MESA website. Calcium Calculator (mesa-nhlbi.org)

Table 1 shows the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles of baseline CAC scores among the white participants in the MESA study. If one hypothesized, for example, that healthy endurance athletes would have CAC scores better that half the total population, this would translate to a CAC score well under 100 for males through their mid 60s and females through their late 70s.

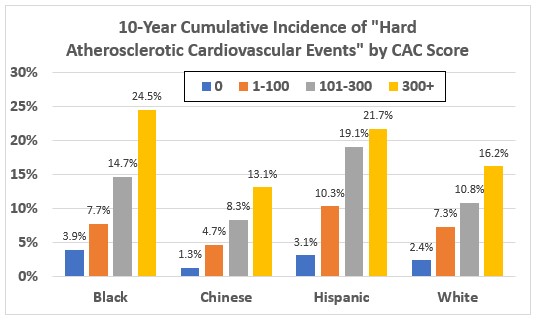

Clinical outcomes for MESA study participants were followed for at least ten years.

Figure 5 shows the 10-year cumulative incidence of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke by race/ethnicity and CAC score. Having a CAC Score of zero (no calcification) was associated with a very low risk. (A zero CAC score is often termed a “warranty against coronary events.”) Having a CAC score of 100 or higher was associated with a 10-year risk of greater than 7.5% in all of the racial/ethnic groups. (Reference #4)

(2c) Clinical Guidelines for Decision-making About Statin Therapies

The current thinking is that statins are the best drug therapy to lower risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events among most individuals with almost any level of LDL-c because of the inflammation-lowering and plaque-stabilizing effects of statins mentioned above. (A newer class of drugs, PCSK-9 inhibitors, may be used for some with very high LDL-c and/or statin intolerance.)

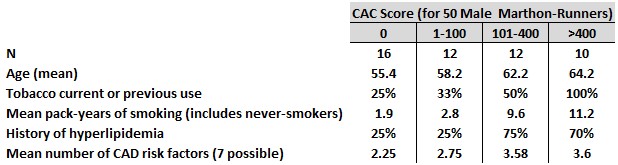

The current American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Multisociety (ten other clinical organizations) guidelines for decision-making about statin therapy (whether to start statins and, if so, what intensity of therapy) use risk calculations based on their “2013 Pooled Cohort Equations (PCE).” (Reference 5)

- The PCE equations calculate risk based on age, sex, race, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, history of diabetes, tobacco use, total blood cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol. See risk calculator at: https://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate/ .

- Updated ACC/AHA risk equations were just announced in November 2023 but practical calculation tools and guidelines for their use have not been published yet. These equations are based on a vastly larger database. (References #6)

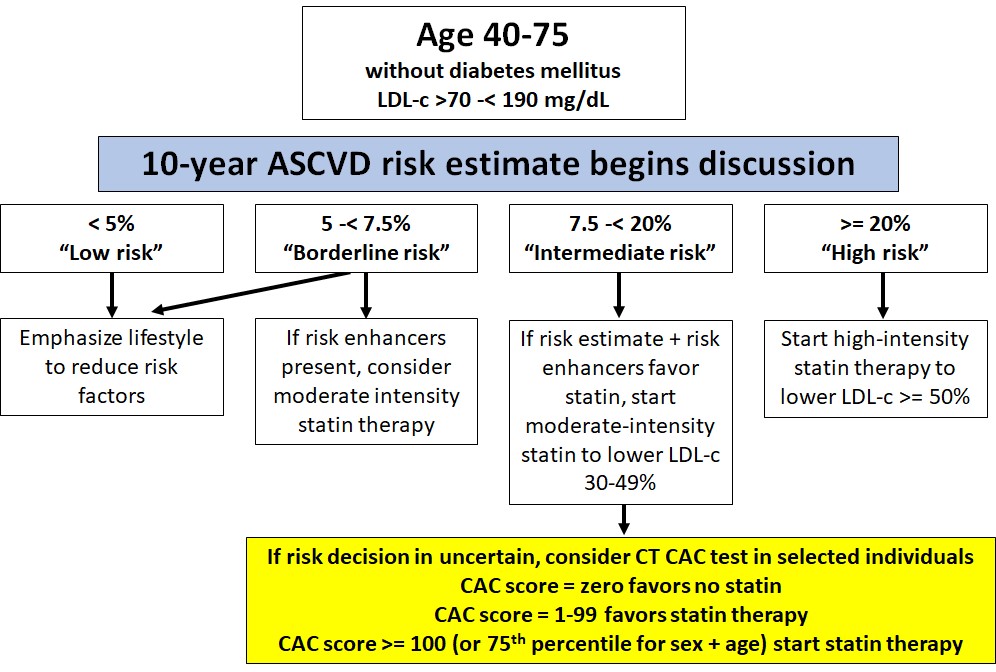

Figures 6a and 6b are a (simplified) outline of the AHA/ACC guidelines decision-making process. I just show the recommendation for patients aged 40-75 without a diagnosis of ASCVD or diabetes or LDL-c >= 190 mg/dL. Decision-making:

- Begins with the 10-year PCE risk estimate;

- Incorporates any additional known “risk enhancers” for the patient (factors not included in the risk equations), and

- May use a CAC score in one specific circumstance – a patient categorized as “Intermediate risk” for whom the “decision is uncertain.”

Following these guidelines, I started “moderate intensity” treatment with a statin (I am using atorvastatin, 20 mg per day) after learning my CAC score.

3.The Studies that Found Evidence that High Volume Endurance Exercise is Associated with Advanced-for-Age Coronary Artery Atherosclerosis

I found six published studies that investigated the association between long-term, high volume endurance exercise and CT evidence of coronary artery atherosclerosis.

(3a) A study of 108 male marathon runners & 216 controls in Germany (Möhlenkamp, et al., 2008)

This was a sub-study by researchers conducting a large study (the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study, HNRS) of the association between CAC score and CAD outcomes in a population-based sample in Germany. (Reference #7)

- By advertising in the German version of Runner’s World magazine, they recruited marathon-runner subjects who were male, older than 50, had completed at least five marathons during the preceding three years, and had no history of diabetes, diagnosed heart disease or angina.

- The controls were drawn from the HNRS study sample. For every marathon-runner subject, they selected two male controls with the same age, body mass index, and Framingham Risk Score (FRS). (The FRS is based on long-term follow-up of cohort from Framingham, Massachusetts. It predicts CAD risk from sex, age, smoking history, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and use of antihypertension medication. The risk equations used in the current AHC/ACC guidelines mentioned above pooled data from the original Framingham cohort with data from four other cohorts.)

- Notably, a little over half of the runners and controls had a smoking history and some (percentage not reported) had high cholesterol and/or hypertension.

Their CAC score findings are briefly described in Table 2. 36% of the marathon-runners had a CAC score >=100 compared to 22% of the controls, which they found to be statistically significant.

(3b) A study of 50 male marathon runners & 23 controls in the U.S. (Schwartz, et al., 2014; Roberts, et al., 2017)

This study recruited runners from the Twin Cities Marathon (TCM) Charter Club – individuals who had run every TCM since the 1982 inaugural event through the 2006 race. The runners were studied in 2006, after their 25th consecutive TCM. At this point, these 50 men (mean age 59.4, age range 46-77) had completed a lifetime total of 3,510 marathons (range 27 to 171 each, mean 70)!

There were two journal articles published from this study. (References #8 and #9)

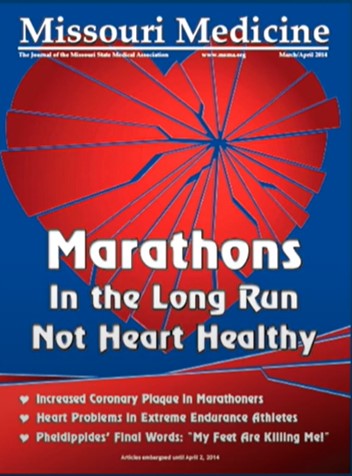

The first article was published in 2014 and described the total amount of plaque, based on CCTA, in marathon runners and a comparison group of 23 “sedentary men who underwent CCTA for clinical reasons.” (They did not describe CAC scores. My guess is their comparison group did not have CAC scores.) The report concluded that “Long-term male marathon runners may have paradoxically increased coronary artery plaque volume.” The article was heralded with a picture on the cover of the medical journal of a shattered heart and the statement, “Marathons: In the Long Run Not Heart Healthy” (see Figure 6). The accompanying editorial, “Pheidipides’ Final Words…” was written by the journal’s editor, a long-time marathon-runner and triathlete who stopped these activities after being horrified to learn he had a high CAC score.

The second publication from this study (2017, in a different journal) described CAC scores for the same 50 marathon-runner subjects and explored differences in history and clinical risk factors among the runners grouped by CAC score (see Table 3). This report concluded, “CACS and CAD are related to CAD risk factors (i.e., age and smoking) and not the number of marathons run or years of running. This suggests that among lifelong endurance athletes, more endurance exercise is not associated with an increased risk of coronary artery plaque formation.”

(3c) A study of 152 male + female endurance athletes & 92 controls in the U.K. (Merghani, et al., 2017)

This study recruited runners and cyclists older than 40 from “elite running and cycling clubs” by advertising in a popular athletic magazine. Controls were recruited through advertisements to staff at three large London hospitals. (Reference #10)

- The athletes were required to have run more than 10 miles or cycled more than 30 miles a week for at least ten years.

- Exclusion criteria for both runners and controls included diagnosed CAD, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, any smoking history, or a family history of premature (younger than 40) CAD.

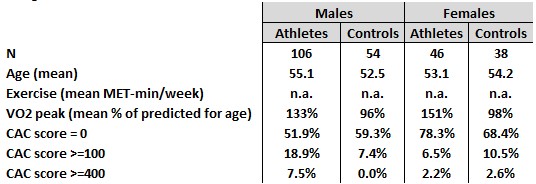

Their CAC score findings are briefly described in Table 4.

- Among the males, 18.9% of the endurance athletes had CAC scores >=100 compared to 7.4% of the controls, which they found to be statistically significant.

- There was a smaller number of females in the study and the results were not found to be statistically significant between the athletes and controls.

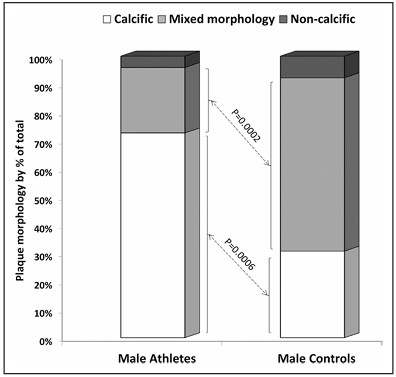

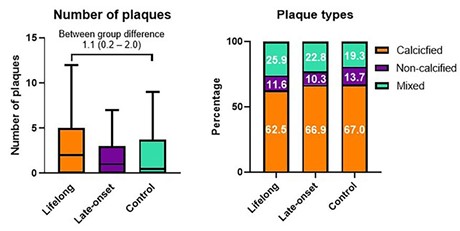

By CTCA:

- More male athletes than controls had greater than two plaques (calcified + non-calcified) and/or any stenosis > 50%.

- Plaques in the endurance athletes were predominantly calcified plaques, while plaques in the controls were predominantly “mixed morphology” plaques (see Figure 7). The authors speculated that “the calcific and stable nature of the plaques among athletic men may … be considered as protective against plaque rupture and acute myocardial infarction” and part of the answer to the apparent paradox that endurance athletes have more atherosclerosis but lower incidence of clinical CAD or death from cardiovascular disease (based on epidemiologic studies such as those I described in my preceding post).

(3d) A study of 318 “middle-aged sportsmen” in the Netherlands (Braber, et al., 2016 and Aerngevaeren, et al., 2017)

The Braber study (MARC, Measuring Athlete’s Risk of Cardiovascular Events) was done to evaluate the potential additional value of adding coronary CT to the recommended sports medical evaluation of older athletes. (Reference #11)

- The participants were recruited “with the help of regional sports physicians” from men 45 or older who “engaged in competitive or recreational leisure sports, were free of known CVD [cardiovascular disease] and had undergone a SME [sports medical evaluation] with bicycle exercise ECG that revealed no abnormalities.”

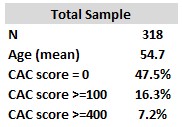

- They found 16.3% of 318 “middle-aged sportsmen” had CAC scores >=100 (Table 5).

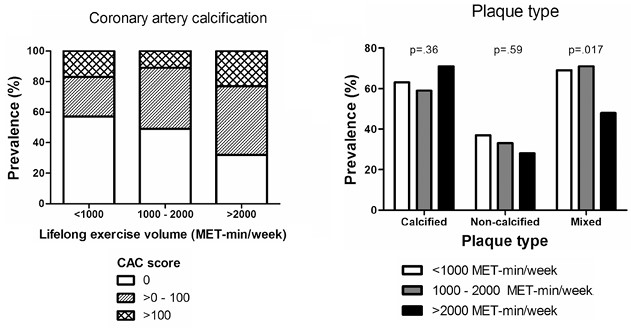

The Aerngevaeren study divided the 318 participants in the MARC study into three comparison groups, based on their estimated “lifelong exercise volume” in MET-mins/week: < 1000, 1000 to 2000, and > 2000. (Reference #12)

Compared with the lowest lifelong exercise volume group (see Figure 8):

- Those in the highest exercise volume group had a statistically significant larger fraction of participants with CAC scores > 100.

- Those in the highest exercise volume group who had plaques, were more likely to have predominantly calcified plaques (those with lower exercise volume were more likely to have mixed or non-calcified plaques).

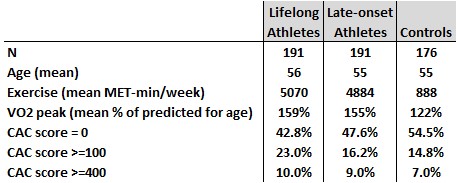

(3e) A study of 191 lifelong male endurance athletes, 191 late onset male endurance athletes, and 176 male non-athletes in Belgium (De Bosscher, et al., 2023)

This is a multi-center prospective study with planned long-term follow-up. The 2023 report is a cross-sectional analysis of participants at the start of the study. (Reference #13)

Males aged 45 and 70 (selected to achieve a balanced age distribution in the three groups) were recruited through a dedicated website that was “advertised to the wide community through media advertisements (e.g., traditional broadcasting, social media, and popular athletic magazines).”

- The athletes indicated regularly cycling >= 8 hours or running >= 6 hours per week. “Lifelong” and “late-onset” athletes started regular endurance exercise before or after age 30, respectively. The majority were cyclists or triathletes.

- The non-athletes did not have a prior history of regular endurance running and engaged in <= 3 hours per week of endurance exercise, though many were runners.

- Exclusion criteria for all three groups included a medical history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or smoking.

Their CAC score findings are briefly described in Table 6. Among the males, 23.0% of the lifelong endurance athletes had CAC scores >=100 compared to 14.8% of the controls, which they found to be statistically significant.

By CTCA:

- More athletes were found to have a greater than two plaques (calcified + non-calcified) and/or any stenosis > 50%.

- As shown in Figure 7 (part of Figure 2 in the article), compared with the controls, the lifelong athletes were more likely to have a larger total number of plaques and have a SMALLER proportion that were calcified plaques. In other words, their findings about plaque composition contradicted those of the Merghani and Aerngevaeren studies.

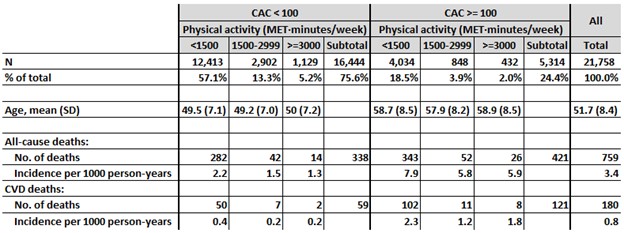

(3f) A study of 21,758 male patients seen at a preventive medicine clinic in the U.S. (DeFina, et al., 2019)

This report used patient data collected at the Cooper Clinic to assess the association among high volumes of physical activity, CAC scores at the start of the study, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality during long-term follow-up. (Reference #14)

They selected male patients who did not have a preexisting myocardial infarction or stroke, and:

- were age 40-80 at the time of their (first) preventive medicine clinic visit, between January 1998 and December 2013;

- provided a detailed history of their physical activity during the three months preceding their clinic visit (completed a questionnaire that was “reviewed with the patient for accuracy”); and

- had a coronary calcium CT (CAC score) and measurements of body mass index, blood pressure, glucose, triglycerides, HDL, and cholesterol, plus smoking history.

Mortality outcomes through 2014 were determined from the National Death Index after a mean follow-up of 10.4 years, during which 759 (3.5%) died.

During the study time period, the Cooper Clinic also saw 9,501 female patients who met the same inclusion criteria. However, only five (0.05%) died, making the longitudinal analysis (reported for males) impossible.

Table 7 describes the sample of 21,758 men by CAC score and physical activity volume categories. 24.4% had a CAC score >=100. 7.2% reported 3,000 or more MET-minutes per week of physical activity. The authors state, “No specific question defined whether these exercisers are in fact competitive athletes (e.g., regular marathon runners)… The mean physical activity volume in the most highly active group was slightly more than… equivalent to running 6 miles/day at a pace of 10 minutes per mile… This exercise volume is consistent with the weekly distances proposed for and practiced by many masters marathon runners.”

Key cross-sectional finding: Men with >= 3000 MET-minutes/week of physical activity were 11% more likely to have a CAC score >= 100, compared with those with less activity, after adjusting for age, BMI, blood glucose and cholesterol, systolic blood pressure and smoking history (relative risk, 1.11, 95% confidence interval, 1.03 – 1.20).

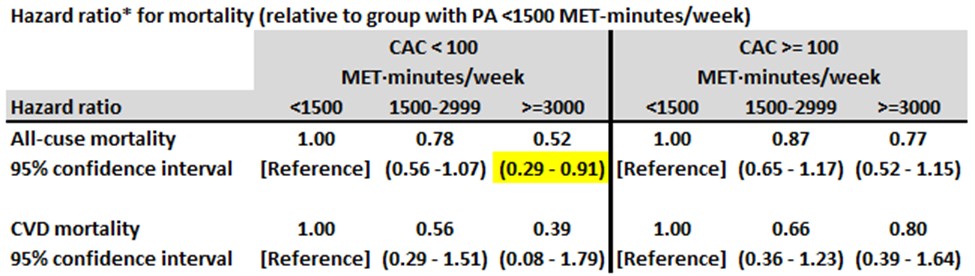

Key findings from long-term follow-up are shown in Table 8. (As in the studies described in my preceding blog post, researchers assumed that PA level in the three months preceding their first clinic visit was strongly associated with PA level during the patients’ follow-up years.)

- Among men with a CAC score < 100, those with >= 3000 MET-mins/week of physical activity were about half as likely to die compared with those with < 1500 MET-mins/week.

- Among men with a CAC score >= 100, those with >= 3000 MET-mins/week of physical activity did not have an increase in all-cause mortality compared with those with < 1500 MET-mins/week.

- The findings for cardiovascular disease mortality were similar.

The authors concluded:

- “These results do not support the contention that high-volume endurance activity with a mean of more than 1 hour of activity per day, increases the risk of all-cause or CVD mortality, regardless of CAC level… Despite …[the] large sample and prolonged follow-up, the number of mortal events in the highest-activity group was remarkably lower.”

- “Once CAC is discovered, a great clinical concern is whether continued high levels of activity accelerate the transition to clinical disease, including nonfatal and fatal CVD events. In the present study, although highly active men had slightly greater risk of CAC of at least 100 AU, a corresponding greater mortality was not seen.”

- “Our findings should reassure patients and their health care professionals that it appears these highly active individuals can safely continue their exercise programs.”

4. Why Are Endurance Athletes More Likely to Have High CAC Scores than Non-Endurance Athletes with the Same Level of Traditional CAD Risk Factors? Could Lipoprotein(a) Level Be a Key Missing Variable in the Studies?

The studies described above are consistent in finding that a larger subset (about eleven percentage points larger) of endurance athletes than of non-endurance athletes had advanced-for-age coronary atherosclerosis (using a CAC score of >= 100 as one definition) that was not explained by traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.

An editorial (Reference #15) in the issue of the journal Circulation that included both the Merghani and the Aerngevaeren articles (see above) states:

- “Although it is possible that the hemodynamic and mechanical factors inherent in endurance exercise may lead to arterial wall injury and recovery calcification, this hypothesis remains speculative. If it were this simple, one would expect CAC to be present in all or at least the vast majority of endurance athlete participants in both studies. Because this was not the case, we are left to consider what factors differentiate those athletes that calcify from those that do not.”

- “Although both studies attempted to adjust for traditional atherosclerotic risk factors, additional potential explanatory factors such as dietary intake, psychological stress, chronic inflammation/anti-inflammatory medication use, and underlying atherosclerotic genetics were not sufficiently adjusted for.”

Some of these “additional potential explanatory factors” could be “confounders” – variables associated with being an endurance athlete and also associated with atherosclerotic risk, but not by mechanisms related to endurance exercise.

A different type of variable that can complicate understanding of a causal relationship is an “effect modifier,” a second variable that changes the effects of the other variable. Figure 12 is a drawing of how I felt on reading the studies above when it occurred to me that a good hypothesis for the finding of high CAC scores in a subgroup of endurance athletes with low traditional factors might be that a more recently appreciated, common CAD risk factor, a high level of lipoprotein(a) – usually spoken as “lipoprotein little a” and abbreviated as Lp(a) – was an effect modifier.

General awareness of Lp(a) increased following reporting of the case of celebrity trainer Bob Harper (from the television show “The Biggest Loser”) who suffered a heart attack in 2018 that was later explained as due to high Lp(a). Awareness was also increased by the work of the (non-profit) Lipoprotein(a) Foundation, which was launched by a 39-year woman (Sandra Tremulis) who discovered she had severe CAD due to high Lp(a). (Reference #16)

Lp(a) is an “LDL-like particle” that differs structurally from LDL in one way, the apo B protein (present in both) is covalently linked to another protein, apo(a), in Lp(a).

- Everyone has Lp(a), but the amount varies among individuals due to presence of different genotypes in a population. Lp(a) level is primarily regulated by two copies (alleles) of the LPA gene, one inherited from each parent.

- Neither lifestyle factors (including diet and exercise) nor any currently available drug therapy can meaningfully lower Lp(a) levels. However, there are now multiple drugs being studied in clinical trials that lower Lp(a).

- Having an Lp(a) level greater than the 80th percentile of the total population is now recognized as an important risk factor for ASCVD (CAD and ischemic strokes) and also for calcification of the aortic valve of the heart. (Reference #17-19)

- Elevated Lp(a) has also been shown to be strongly associated with elevated CAC scores among individuals currently without signs or symptoms of ASCVD. (References 20 and 21)

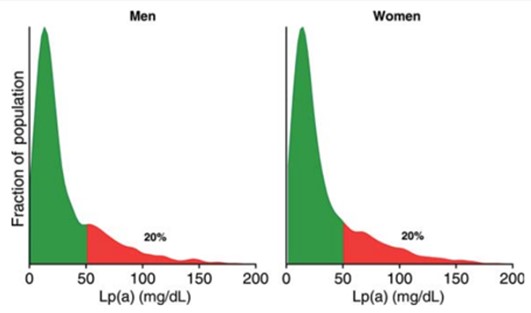

Figure 13 shows the distribution of Lp(a) levels in the general population. Most individuals have Lp(a) levels within a fairly small range (green area in the figure) but there is a long right “tail” in the distribution (red area), consisting of individuals with the much higher Lp(a) levels that have been shown to increase risk for CAD. (Reference 18)

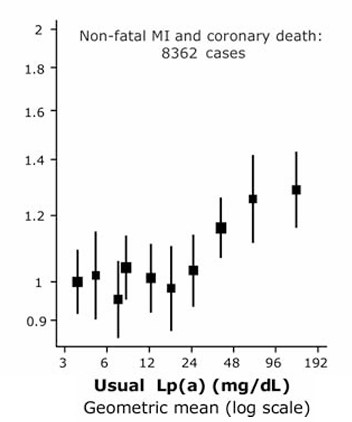

Figure 14 shows the association between Lp(a) level and relative risks of coronary heart disease. Lp(a) levels greater than the 80th percentile for the population (>= 50 mg/dL) were associated with >= 20% increased risk (after statistically adjusting for traditional risk factors). (Reference #18)

In a random sample of individuals, elevated Lp(a) would be equally likely among endurance athletes and non-endurance athletes and would not explain why a larger subset of athletes would have advanced-for-age atherosclerosis, except by chance. However, it seems biologically plausible (to me) that the combined effects of BOTH high Lp(a) AND long-term vigorous exercise — injury to the endothelium of coronary arteries presumably causes increased permeability to both LDL and (the more atherogenic) Lp(a) particles — might explain the findings in the studies discussed above – that is, a subset of endurance athletes with increased-for-age coronary atherosclerosis.

- I have yet to find any medical studies or other articles that discuss BOTH the effect of running on the coronary arteries AND the effect of high Lp(a).

- Lp(a) levels were not measured in any of the studies above, which seems like an important omission to me. (The De Bosscher study is ongoing, with planned follow-up examinations of the participants, so they could probably determine levels in their study sample to see if high Lp(a) was associated with being in the subsets of endurance athletes and non-athletes with increased plaques — if they thought this was worth the expense.)

More about me: I subsequently got lab test results for three “risk enhancers” (see Figure 6a) I had not previously had assessed (hs-CRP, ApoB, and Lp(a)). My hs-CRP and ApoB levels were both quite low (good). Alas (double yikes), I learned I have a LpA level at the 80th percentile. My moderate intensity statin therapy lowered my LDL-c to below 50 mg/dL.

5. Risk of the Bad Outcomes of CAD in Endurance Athletes with Increased-for-Age Coronary Atherosclerosis

None of the five studies (above) of people specifically identified as endurance athletes and controls, have long-term follow-up of study subjects to determine if the subset with increased-for-age coronary atherosclerosis had a higher incidence of MIs or sudden cardiac death – though this is part of the study plan for the De Bosscher study.

The sixth study (DeFina), from the Cooper Clinic, analyzed long-term outcomes (all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality) for all patients with a CAC score at their initial clinic visit, stratified by their CAC score and reported amount of PA.

- The report did not compare outcomes in the high PA group with CAC scores >= 100 versus those in the high PA group with lower CAC scores. Presumably having a high CAC score was associated with worse outcomes, as in the MESA study, at least because the population of individuals drawn to endurance exercise includes many who have well-established risk factors for atherosclerosis in addition to its (possible) acceleration by endurance exercise.

- Their results suggest that, among those with CAC scores >100, those in the highest PA group had better outcomes than those in the lower PA groups. However, there were too few Cooper Clinic patients with PA >= 3000 MET-minutes/week for their results to achieve statistical significance, so they were only able to state that high PA was not associated with worse outcomes.

6. My Current Thoughts About Endurance Exercise & Risk from Coronary Artery Disease

For now, my working assumption is that many benefits from a high volume of endurance exercise (see preceding post) meaningfully offset the combined negative effects of very many of the factors known or suspected of increasing the risk of coronary artery disease (including endurance exercise itself). Not engaging in a lot of endurance exercise for as long as I am able to (in my life course), I suspect, would have a (strong) net negative effect on my health and happiness.

However, I plan to continue efforts to find and understand current and future evidence related to “the extreme exercise hypothesis.”

References

Copies of all the references I cite were downloaded for free from online sources. If you are interested in any, I recommend entering the title of the article in a search engine like Google, then looking through the results for those that require no payment.

- Franklin BA, Eijsvogels TMH, Pandey A, Quindry J, Toth PP. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and cardiovascular health: A clinical practice statement of the ASPC Part I: Bioenergetics, contemporary physical activity recommendations, benefits, risks, extreme exercise regimens, potential maladaptations. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022 Oct 13;12:100424.

- van Rosendael AR, van den Hoogen IJ, Gianni U, Ma X, Tantawy SW, Bax AM, Lu Y, Andreini D, Al-Mallah MH, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Chinnaiyan K, Choi JH, Conte E, Marques H, de Araújo Gonçalves P, Gottlieb I, Hadamitzky M, Leipsic JA, Maffei E, Pontone G, Shin S, Kim YJ, Lee BK, Chun EJ, Sung JM, Lee SE, Virmani R, Samady H, Sato Y, Stone PH, Berman DS, Narula J, Blankstein R, Min JK, Lin FY, Shaw LJ, Bax JJ, Chang HJ. Association of statin treatment with progression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque composition. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 Nov 1;6(11):1257-1266.

- McClelland RL, Chung H, Detrano R, Post W, Kronmal RA. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2006 Jan 3;113(1):30-7.

- Budoff MJ, Young R, Burke G, Jeffrey Carr J, Detrano RC, Folsom AR, Kronmal R, Lima JAC, Liu KJ, McClelland RL, Michos E, Post WS, Shea S, Watson KE, Wong ND. Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur Heart J. 2018 Jul 1;39(25):2401-2408.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC Jr, Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jun 25;73(24):3168-3209.

- Khan SS, Coresh J, Pencina MJ, Ndumele CE, Rangaswami J, Chow SL, Palaniappan LP, Sperling LS, Virani SS, Ho JE, Neeland IJ, Tuttle KR, Rajgopal Singh R, Elkind MSV, Lloyd-Jones DM; American Heart Association. Novel prediction equations for absolute risk assessment of total cardiovascular disease incorporating cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic Health: A scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023 Dec 12;148(24):1982-2004.

- Möhlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Breuckmann F, Bröcker-Preuss M, Nassenstein K, Halle M, Budde T, Mann K, Barkhausen J, Heusch G, Jöckel KH, Erbel R; Marathon Study Investigators; Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigators. Running: the risk of coronary events : Prevalence and prognostic relevance of coronary atherosclerosis in marathon runners. Eur Heart J. 2008 Aug;29(15):1903-10.

- Schwartz RS, Kraus SM, Schwartz JG, Wickstrom KK, Peichel G, Garberich RF, Lesser JR, Oesterle SN, Knickelbine T, Harris KM, Duval S, Roberts WO, O’Keefe JH. Increased coronary artery plaque volume among male marathon runners. Missouri Medicine. 2014 Mar-Apr;111(2):89-94.

- Roberts WO, Schwartz RS, Garberich RF, Carlson S, Knickelbine T, Schwartz JG, Peichel G, Lesser JR, Wickstrom K, Harris KM. Fifty men, 3510 marathons, cardiac risk factors, and coronary artery calcium scores. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Dec;49(12):2369-2373.

- Merghani A, Maestrini V, Rosmini S, Cox AT, Dhutia H, Bastiaenan R, David S, Yeo TJ, Narain R, Malhotra A, Papadakis M, Wilson MG, Tome M, AlFakih K, Moon JC, Sharma S. Prevalence of subclinical coronary artery disease in masters endurance athletes with a low atherosclerotic risk profile. Circulation. 2017 Jul 11;136(2):126-137.

- Braber TL, Mosterd A, Prakken NH, Rienks R, Nathoe HM, Mali WP, Doevendans PA, Backx FJ, Bots ML, Grobbee DE, Velthuis BK. Occult coronary artery disease in middle-aged sportsmen with a low cardiovascular risk score: The Measuring Athlete’s Risk of Cardiovascular Events (MARC) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016 Oct;23(15):1677-84.

- Aengevaeren VL, Mosterd A, Braber TL, Prakken NHJ, Doevendans PA, Grobbee DE, Thompson PD, Eijsvogels TMH, Velthuis BK. Relationship between lifelong exercise volume and coronary atherosclerosis in athletes. Circulation. 2017 Jul 11;136(2):138-148.

- De Bosscher R, Dausin C, Claus P, Bogaert J, Dymarkowski S, Goetschalckx K, Ghekiere O, Van De Heyning CM, Van Herck P, Paelinck B, Addouli HE, La Gerche A, Herbots L, Willems R, Heidbuchel H, Claessen G. Lifelong endurance exercise and its relation with coronary atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2023 Jul 7;44(26):2388-2399.

- DeFina LF, Radford NB, Barlow CE, Willis BL, Leonard D, Haskell WL, Farrell SW, Pavlovic A, Abel K, Berry JD, Khera A, Levine BD. Association of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality with high levels of physical activity and concurrent coronary artery calcification. JAMA Cardiol. 2019 Feb 1;4(2):174-181.

- Baggish AL, Levine BD. Coronary artery calcification among endurance athletes: “Hearts of Stone”. Circulation. 2017 Jul 11;136(2):149-151.

- O’Connor A. A heart risk factor even doctors know little about. New York Times. 2018 Jan 9.

- Reyes-Soffer G, Ginsberg HN, Berglund L, Duell PB, Heffron SP, Kamstrup PR, Lloyd-Jones DM, Marcovina SM, Yeang C, Koschinsky ML; American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Lipoprotein(a): A genetically determined, causal, and prevalent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022 Jan;42(1):e48-e60.

- Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, Borén J, Andreotti F, Watts GF, Ginsberg H, Amarenco P, Catapano A, Descamps OS, Fisher E, Kovanen PT, Kuivenhoven JA, Lesnik P, Masana L, Reiner Z, Taskinen MR, Tokgözoglu L, Tybjærg-Hansen A; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J. 2010 Dec;31(23):2844-53.

- Patel AP, Wang, M, Pirruccello JP, Ellinor PT, Ng K, Kathiresan S, Khera AV. Lp(a) (Lipoprotein[a]) Concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: New insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021 Jan;41(1):465-474.

- Lee H, Park KS, Jeon YJ, Park EJ, Park S, Ann SH, Kim YG, Lee Y, Choi SH, Park GM. Lipoprotein(a) and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2022 May;349:190-195.

- Singh SS, van der Toorn JE, Sijbrands EJG, de Rijke YB, Kavousi M, Bos D. Lipoprotein(a) is associated with a larger systemic burden of arterial calcification. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023 Jul 24;24(8):1102-1109.

Leave a comment