I have almost reached the start of my 66th year and am, as far as I know, in excellent health. This puts me at high risk of living far into the age ranges in which a terrifying percentage of people develop dementia (pathologic cognitive decline severe enough to interfere with daily life). I have a brother and three sisters (see Figure 1) who are all older than me and, thankfully, none show signs of pathologic cognitive decline as far as I know. However, my dad died from Alzheimer’s disease in 2009 at age 84. Then, eight months ago, my mom passed away at age 94, after eight and half years of care in a skilled nursing home due to advanced dementia. (My mom’s diagnosis would probably have been “vascular dementia” or “mixed dementia” rather than Alzheimer’s but she was never formally evaluated.) I have dreaded the possibility of living with dementia since long before it devastated my parents. Witnessing their experiences has not diminished my dread.

A key life strategy for me is planning to run (a lot) for as long as I am able and to continue (a lot) of other physical activity when I am not able to run, mostly because of the joy and awe being active facilitates. I am, of course, very interested in the possibility that this lifestyle choice may also reduce my chances of an unwelcome or a terrifying cognitive trajectory, even though that is not the primary reason I seek to have a high level of physical activity.

- Estimating How Much Longer I may Live.

- Estimating the Probability that I will Develop Dementia

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is Even More Likely

- For Sure, I will Continue “Normal Age-Related Cognitive Decline”

- Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors for Dementia

- The Monsters in the Closet: Genes that Increase Dementia Risk

- Studies of Association Between Physical Activity (PA) and Dementia or MCI

- An Observational Study of Runners I would Like to See Extended

- How PA May Protect Against Normal Cognitive Aging, MCI, and Dementia

- I would Love to See Results of a Study of Endurance Running & Brain Health

Estimating How Much Longer I may Live.

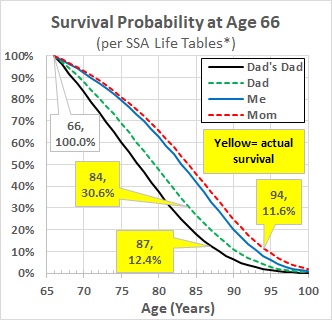

In Figure 2:

- The solid blue line labelled “me” is the probability of a 66-year-old male surviving to the age on the horizontal axis, based on the most recent Social Security Administration (SSA) Life Table, which describes 2019 deaths by age for the U.S. population. (See reference 1 at end of this blog.)

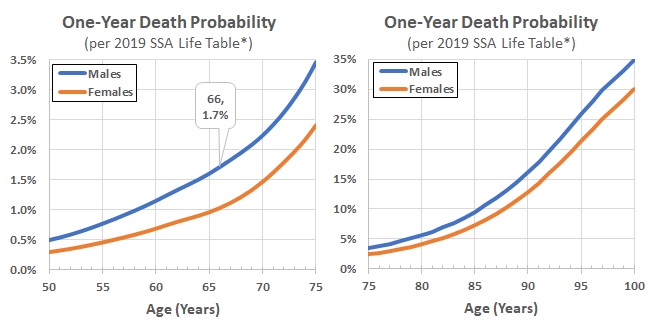

- Figure 3 plots the one-year 2019 death rates by age from this life table for males and females aged 50 to 100.

- I calculated the survival probabilities by age in Figure 2 by sequentially multiplying one-year survival (= one minus the death rate for each one-year interval) times the calculated probability of surviving to the preceding age, beginning with a 100% probability at 66.

- The dashed red line (“Mom”) and dashed green line (“Dad”) are the probabilities of a female and male surviving past 66, based on the 1990 SSA Life Table (closest available online to the years Mom and Dad were 66).

- The solid black line (“Dad’s Dad”) is the probability of a male surviving past age 66, based on the 1960 SSA Life Table (closest available online to the year Granddad was 66).

- This SSA life table analysis predicts that 50% of all U.S. males at my current age will still be alive at age 83.

- This compares with predictions, using the same methodology, of about 50% still alive at about 79 and 77, for the two previous generations of males in my family.

- Both my parents and my grandfather survived longer than the predicted median: Dad to age at which all but 30.6% were predicted to have died, Mom 11.6%, Granddad 12.4%.

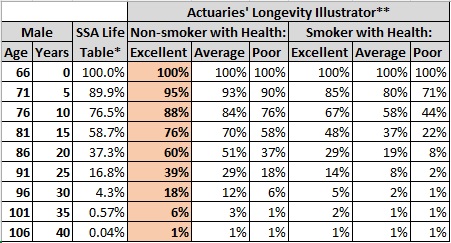

The current “Actuaries’ Longevity Illustrator” also uses 2019 SSA Life Table data but refines predictions by applying estimates of continued mortality improvement in the U.S. and stratifies results by Smoker vs. Non-smoker and how you would rate your “General Health” (excellent, average, or poor). Figure 4 shows their predictions for a 66-year-old male. As a non-smoker who thinks he is in excellent health, this tool predicts a 50% probability that I will die at an age of 88 or later (18% at 96 or later). (Reference 3.)

There are many online calculators that spit out a single age-at-death prediction based on various attributes you enter. For example, the John Hancock (insurance company) calculator has you enter the following: male/female; smoker/non-smoker; age; height; weight; blood pressure normal/medicated/high; cholesterol normal/medicated/high; exercise daily/weekly/monthly; alcohol consumed per week; and number of traffic violations in last year. It then makes a point estimate of when you are most likely to die. For me, it calculates age 96 years. (Reference 4.) I find the fuller range of the longevity estimates discussed above more helpful. I think it is useful to have some idea of the likelihood that I could die in the not-so-distant future as well as the likelihood that I will still be around at very old ages.

Estimating the Probability that I will Develop Dementia

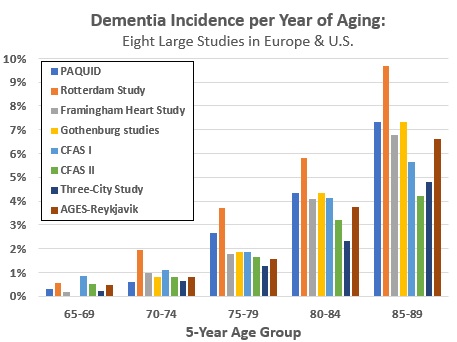

The best estimates I have found of the probability of developing dementia by age are from a research paper that pools the results from eight large longitudinal studies that followed representative samples of people in the U.S., France, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Iceland. (Reference 5.)

Figure 5 shows each study’s estimates of the all-cause dementia incidence rate (percentage developing dementia) per year by five-year age groups from 65 to 89.

- Incidence rates calculated as a simple average of the eight estimates in this paper approximately double with each 5-year increase in age: 0.4% per year from ages 65 to 69, 1.0% per year from 70 to 74, 2% per year from 75 to 79, 4% per year from 80 to 84, and 6.6% per year from 85 to 89.

- I can use these numbers to calculate an estimate of the chances of a 66-year-old remaining “dementia-free.” For example:

- If still alive at age 68, the probability of no dementia = (1 – 0.004) * (1 – 0.004) = (1 – 0.004)2 = 99.2%.

- If still alive at 90, the probability of no dementia = (1 – 0.004)4 * (1 – 0.01)5 * (1 – 0.02)5 * (1 – 0.04)5 * (1 – 0.066)5 = 49.0%.

- This objective of the scientific paper was to pool the individual study results to estimate the trend in by-age incidence of dementia in Europe and the U.S. by ten-year date of birth intervals.

- The authors concluded that the incidence of dementia decreased at a rate of 13% per decade between 1988 and 2015 in these high-income countries.

- Hopefully, it would be reasonable to use lower by-year-of-age probability estimates for me, based on this trend.

- If I assume incidence rates per year that are 39% lower than above, the same calculation gives a probability of no dementia at age 90 = 65% (35% of having dementia).

- The total number of people living with dementia will continue to increase throughout the coming decades, due to the expected large increase in the number of older people in the population. However, if this trend continues, the associated economic and other burdens on society may be lower than previously estimated.

- The authors concluded that the incidence of dementia decreased at a rate of 13% per decade between 1988 and 2015 in these high-income countries.

Note: “All-cause dementia” is a collective name for a large set of brain syndromes that affect memory, thinking, behavior, and emotion, and eventually result in the need for help with all aspects of daily living. (Reference 6.)

- Something like 90% of cases are Alzheimer’s disease (the most common cause of dementia – 50% to 75% of all cases), vascular dementia, or mixed dementia (e.g., pathologic characteristics of both vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s).

- Some other types include Lewy body dementia with or without preceding Parkinson’s disease (actor/comedian Robin Williams’ case increased public awareness of this diagnosis) and fronto-temporal dementia (actor Bruce Willis’ case increased public awareness of this diagnosis).

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is Even More Likely

MCI is a clinical diagnosis of “symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education, but that do not interfere with his or her independence.” (Reference 7.) A much larger percentage of the population experiences MCI than dementia, and for longer periods of life. (Reference 8.)

- Ideally, a diagnosis of MCI is based on formal neuropsychological testing and clinical evaluation.

- Many patients with this diagnosis have “preclinical Alzheimer’s disease” and will go on to develop more severe cognitive impairment that meets clinical criteria for dementia. That is, if they live long enough.

- Even without (or before) development of more severe cognitive decline, MCI may cause disability and a poorer quality of life.

For Sure, I will Continue “Normal Age-Related Cognitive Decline”

Most older adults notice (Reference 9):

- An overall (mild) slowing of thinking,

- Some slowing of word-finding and recalling names,

- Mild decrease in ability sustain attention, and

- A slight decrease in ability to hold information in the mind while multitasking

I am very aware and annoyed by my own increase in slowness of word/name finding. (Curiously, the word or name I struggle to find will often suddenly pop into mind hours later. Some recent examples: “The Basilica,” which is a Catholic church that is a major landmark in Minneapolis; former Minnesota governor Jesse Ventura; and singer Justin Bieber. I now recall the name Basilica by thinking of it as “a base of Catholic operations,” with lots of priests and parishioners scurrying about. Jesse Ventura and Bieber are now sitting in a Basilica pew in my mind. For some reason, Justin Timberlake and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau are next to them.)

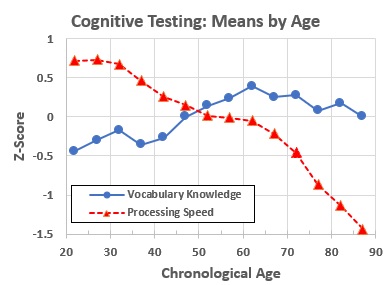

Neuropsychological testing generates standardized measures of different aspects of cognition. One common simplification of many of these measures lumps them into two groups (Reference 10):

- Fluid intelligence, which refers to “measures representing efficiency or effectiveness of processing carried out at the time of assessment.” This includes “a person’s ability to process and learn new information, solve problems, and attend to and manipulate one’s environment.” Measures of many “fluid” cognitive abilities peak in the 30s and then steadily decline throughout remaining life. Examples include processing speed, working memory, and long-term memory (for example, cued and non-cued recall).

- Crystallized intelligence, which refers to “measures representing products of processing carried out in the past, such as vocabulary or general information in which the relevant acquisition occurred earlier in one’s life.” In contrast to fluid intelligence, these measures increase (people perform better as they grow older) at least until people are in their 60s.

- Figure 6 shows the changes with age of the mean results for two neuropsychologic test measures.

Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors for Dementia

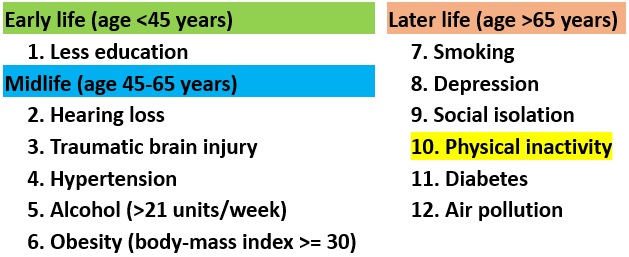

- The most authoritative evaluation I have found of “potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia” is the 2020 report by the Lancet Commission, which assembled an “international group of experts [who] presented, debated, and agreed upon the best available evidence.” (Reference 11.)

- This report identifies 12 well-established negative risk factors (bad things), which it presents as associated with different phases in a “life-course model” (see Figure 7).

The Lancet Commission report reviewed but did not decide to list as well-established risk factors:

- Diet. If you read newspapers or do internet searches on preventing dementia you will probably see a lot of discussions about the brain health benefits of the Mediterranean Diet or the MIND Diet in comparison with the so-called “Standard American Diet (SAD).” (References 12 & 13.)

- Sleep. This is a hot topic. For example, there is evidence of the role of the slow-wave sleep (“deep sleep”) in the “glymphatic system” of the brain that appears to remove soluble β-amyloid from the brain. Reduced amounts of deep sleep may be an important modifiable risk factor. (References 14 & 15.)

- Later life cognitively stimulating activities. There is also a lot of information out there about the potential value of things like learning a new language or musical instrument, developing new hobbies and interests, etc. Using commercial a “brain-training app” (examples include Elevate, Lumosity, or Cognifit) represents another type of strategy that is widely promoted by the companies that sell them.

The Lancet Commission report also does not include targets for pharmacologic therapies as potentially modifiable risk factors. However, there are now two anti-amyloid drugs that are FDA-approved and at least one of them has evidence of efficacy – the approval of aducanumab (AduhemTM ) is very controversial. Other anti-amyloid drugs are in stage 3 clinical trials.

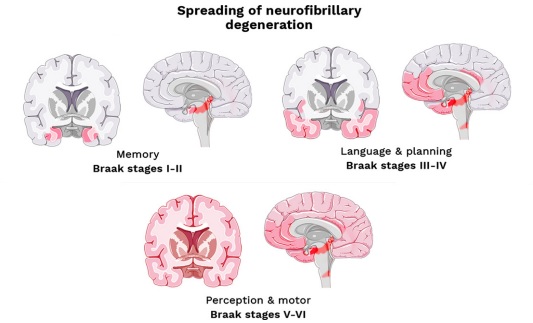

- Abnormal accumulation of β-amyloid protein in the brain has been the target of many experimental drugs to treat Alzheimer’s disease.

- Accumulation of misfolded β-amyloid protein as extra-cellular amyloid plaques in the brain has long been hypothesized to be the initial insult that triggers pathways to dementia.

- This is followed by accumulation of abnormal tau protein within neurons and formation of neurofibrillary tangles, which are hypothesized to cause losses of synapses (connections between brain neurons) and brain neuron death that result in cognitive impairment and dementia. (Reference 16.)

- Amyloid and tau accumulation may be underway for one or two decades before clinical symptoms occur, analogous to the accumulation of cholesterol plaques in blood vessels decades before the occurrences of symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (such as heart attack and stroke).

- The hope has been that effective “secondary” and “primary” prevention drug therapies for Alzheimer’s could be developed, analogous to the development of statin drugs to lower LDL-cholesterol and decrease risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

- On January 6, 2023, lecanemab (Leqembi™), a monoclonal antibody the binds to β-amyloid was given accelerated approval by the FDA for treatment of early-stage Alzheimer’s. (Reference 17.)

- Approval was based on clinical trial results showing it dramatically reduced amyloid plaques and modestly slowed cognitive decline after 18 months of treatment, compared with those who received a placebo.

- The price of lecanemab is $26,500 per year for the average patient plus additional costs for its intravenous infusion and periodic MRI brain scans to monitor for adverse effects. Currently Medicare does not pay for either lecanemab or aducanumab.

The Monsters in the Closet: Genes that Increase Dementia Risk

I believe my life so far puts me on the favorable side of all the risk factors in Figure 7, which by itself would suggest my probability of dementia may be lower than the population incidence estimates above. However, the most important risk factors are in an individual’s genetic makeup and unmodifiable.

- Having one primary relative with Alzheimer’s disease, in my case my dad, is an unfavorable risk factor.

- The best-known worry-about gene is APOE. An individual has one APOE gene from each parent. The most common APOE gene is the ε3 allele (version of the gene). Compared with having two ε3 alleles:

- Having one APOE ε4 allele increases late-onset Alzheimer’s risk three-fold,

- Having two ε4 alleles increases risk at eight- to 12-fold, and

- Having the ε2 allele (rare) is associated with lower risk.

- Commercial gene sequencing companies provide direct-to-consumer APOE information. The risk numbers above are from 23andMe, which also shows the prevalence of the different genotypes by ethnicity based on their customers’ results. (Reference 18.)

- I do not know my APOE genotype and do not currently see why I would want to.

Studies of Association Between Physical Activity (PA) and Dementia or MCI

Most epidemiological studies that have looked, have shown a statistical association between PA and the incidence of dementia or MCI among cohorts of subjects followed for years.

- This is widely accepted as strong evidence of a causal relationship, when combined with some other types of evidence that support plausibility. However, statistical association by itself may be not reflect a true causal relationship as it could be explained by “confounding” (association with other factors that are the actual cause) or wrong temporal relationship (“reverse causation” is a concern if studies could include subjects who have lower PA because they had already developed MCI or dementia when PA was measured).

- The gold standard of evidence is usually the randomized controlled trial, which would be very difficult for this question because of long time periods required, the difficulty of getting clear differences between the intervention and control groups, and the ethics of such a study. There are a lot of published short experimental studies involving interventions in groups of subjects (usually physically inactive people at baseline), but I find these studies very hard to interpret.

General method of epidemiological studies looking at association of PA and dementia.

- Assemble a large cohort of (“midlife” or “later-life”) subjects. Apply a method to assess cognition so that those who, at the start, already have dementia can be excluded from study.

- Measure each subject’s habitual level of PA. This usually been done by a questionnaire, but I came across a couple that had subjects wear wrist accelerometers. I found two studies that, alternatively, measured cardiorespiratory fitness at the start.

- Measure various attributes that might confound the association between PA and dementia (such as APOE genotype, formal education, socioeconomic status, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, etc.).

- Determine which subjects developed dementia (or MCI) during the study follow-up period (which needs to be many years).

- Apply statistical methods to estimate risk (association between PA and dementia or MCI), adjusting for possible confounders.

The most helpful studies I have found so far are:

Study A. A meta-analysis of pa and AD

- A meta-analysis that identified all cohort studies mentioning both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and PA that were published between 1966 and 2015, then limited analysis to those studies which had subjects who were 65 years or older at study start. (Reference 19.)

- The authors included nine studies that together had a total of 20,326 participants, of whom 1,358 (6.7%) developed dementia after a mean length of follow-up ranging from four to seven years. Their meta-analysis estimated a 39% lower risk (95% confidence interval 27% to 48% lower risk) of AD was associated with being physically active compared to non-active (after statistically adjusting for potential confounding variables). The methods of assessment of PA in most of the individual studies did not allow for very good assessment of “dose effect” (i.e., subcategorization of “physically active” subjects based on how active they were).

- This meta-analysis (and B, below) are the key studies cited by the Lancet Commission Report (above) to support their conclusion that there is strong evidence PA is associated with lower risk of dementia.

study b. A meta-analysis of pa and cognitive delcine not dementia

- A meta-analysis that identified all longitudinal studies published between 1966 and 2010 that investigated the association between PA and “cognitive decline” (not dementia) in older adults who had normal cognition at the start. In most of the studies, cognition at the start and end was measured using the min-mental status exam (MMSE). (Reference 20.)

- The researchers included 15 studies that together had a total of 33,816 participants, of whom 3,210 (9.5%) showed cognitive decline (but not dementia) after follow-up ranging from one to twelve years.

- The meta-analysis estimated a 38% lower risk (95% confidence interval 30% to 46% lower risk) of cognitive decline was associated with a higher level of PA compared with being inactive (after statistically adjusting for potential confounding variables).

- As above, the methods of assessment of PA in most of the individual studies did not allow for very good assessment of “dose effect” (i.e., subcategorization of “physically active” subjects based on just how active they were).

study c. Framingham study

- A report on results from the Framingham Study that was published in 2017. This study would presumably have been included in the meta-analysis (A) above, had it been published earlier. It also included a study of the association between physical activity and brain MRI findings. (Reference 21.)

- PA was assessed for 3,714 Framingham Study Original and Offspring cohorts at age 60 or older who were cognitively normal at the start.

- 236 (6.4%) of the 3,714 developed dementia during the following ten years (for 188 [80%] the diagnosis was Alzheimer’s disease). They estimated that the more active subjects had 50% lower risk (95% confidence interval 3% to 96% lower risk) of all-cause dementia than the least active (after statistically adjusting for potential confounding variables).

- The additional study performed brain MRIs on the 1,987 Offspring cohort members. They found higher PA was associated with higher total brain volume and hippocampus volume. This is an interesting contribution since many authors suggest that physical activity may protect against dementia by exercise-induced increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) – see below.

Study d. ARic study

- A report on results from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study that was published in 2019. They studied both dementia and MCI. (Reference 22.)

- PA was assessed by a detailed interviewer-administered questionnaire for 10,705 adults at “mid-life” (mean age 60) and again six years later. Subjects had a median follow-up of 17.4 years.Cognitive status was assessed by an expert panel based on neuropsychological test performance, standardized functional assessments and neurological exams.1,063 (9.9%) developed dementia. Compared with the lowest category of PA, high PA was associated with a 29% lower risk of dementia (95% confidence interval 24% to 39% lower risk).

- Compared with the highest category of PA, the lowest category of PA was also associated with a higher rate of cognitive decline. This equated to “roughly a 12% greater cognitive decline from mid- to late-life.” High PA was associated with less cognitive decline compared to low or middle PA.

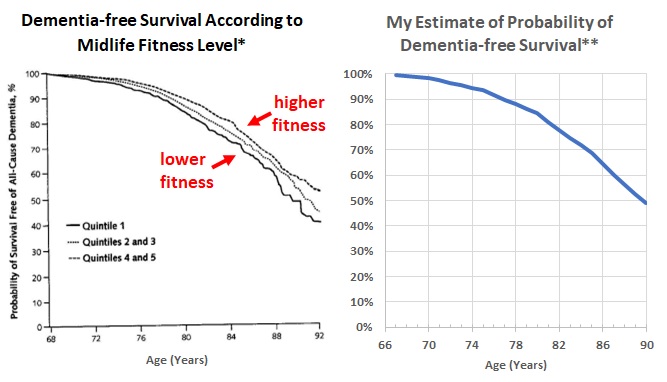

study e. cooper center longitudinal study

- A report from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study (CCLS) investigates the association between mid-life cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) rather than PA. I suspect that CRF may be a more objective measure of PA than a questionnaire (but CRF also has a significant genetic component). (Reference 23.)

- The Cooper Clinic in Dallas, Texas, is a preventive medicine practice founded in 1970 by Kenneth Cooper, M.D. (who invented the term “aerobics”). Patients seen at the clinic have provided informed consent for the use of their data for research by the CCLS. This report was based on 19,458 adults who had their CRF measured in mid-life (mean age about 50) by a treadmill test between 1971 and 2009 and could be matched with Medicare administrative claims data between 1999 and 2009. Diagnosis codes of medical claims were used to identify incident cases of all-cause dementia. 1,659 (8.5%) of the 19,458 developed dementia during a mean follow-up time of 24 years. Compared with the lowest quintile of CRF (lowest fifth of their study subjects by CRF), those in the highest quintile had a 36% lower risk of dementia (95% confidence interval 23% to 47% lower risk).

- The left side of Figure 7 (modified from the report) shows the percentage of patients by age who were still alive and dementia-free, stratified by their mid-life CRF. The right side of Figure 7 plots the probability, by age, I calculated (above) that someone dementia-free at age 66 would survive dementia-free, using the dementia incidence estimates shown in my Figure 4.

study f. a study using veterans administration medical records

- Another study that looked at the association between CRF and incidence of dementia got a lot of coverage in newspapers. As far as I can tell, this has only been published as an abstract (from a poster presented at the American Academy of Neurology meeting in April 2022), so details of the study and potentially important contributions from peer review (typically a part of publishing in a medical journal) are not available. I am hoping they will publish a more complete report. (Reference 24.)

- The researchers used the very extensive electronic medical record system of the U.S. Veteran’s Administration to identify 649,605 veterans who completed standardized treadmill testing and were free of dementia at the time of testing. They then retrospectively followed these by using their medical records over an average of 8.8 years of follow-up to identify which developed dementia.

- With this very large sample size, the study was able to get more precise estimates of risk. They divided the study sample by age-specific fitness into five equally sized groups. Compared to the lowest-fit group, the risks of incident dementia associated with low-, moderate-, high-, and highest-fit groups were 13%, 20%, 26% and 33% lower, respectively.

An Observational Study of Runners I would Like to See Extended

While trying to describe the results of the studies above, I was struck by how similar the estimates of the association of increased PA and decreased risk of dementia (or MCI) are between the studies.

- This could be an indication that they are close to being “correct.”

- However, I would guess that there is a large amount of misclassification of the level of PA because of the limitations of determining this with questionnaires (does not apply to treadmill test classification, though) and the frequency with which people’s level of PA changes when other things change in their lives (applies to however PA is measured when just measured at one time point). Such misclassification, if random, would be expected to decrease the measured strength of association – that is, underestimate the effect of higher PA on brain health.

One set of people that I think would be very interesting to study is older runners, who often have developed a very important-to-them personal identity as someone who runs a lot, takes care of their health, etc. Those who temporarily or permanently lose their ability to run often adjust their identity to “someone who regularly does a lot of (other) vigorous exercise, such as biking, brisk walking, swimming, Nordic skiing, paddling, etc.” Studying older runners could help determine whether (a lot) more PA has an even larger effect on brain health.

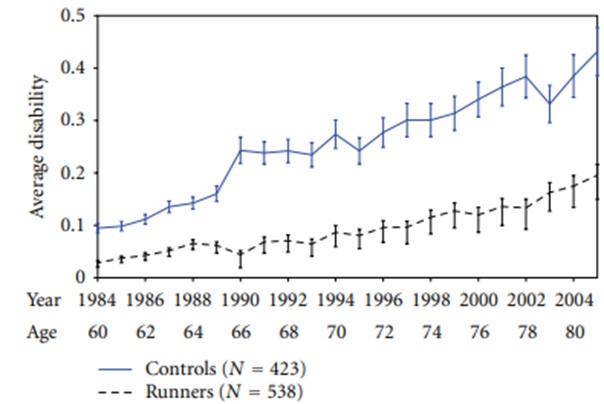

There is at least one prospective running study for which I am hoping someone may report new analysis after additional years of follow-up. This is the Stanford Runners’ Study started in 1984 by James Fries, M.D., famous for promoting the “compression of morbidity” hypothesis: “While a healthy lifestyle modestly extends longevity, it more effectively staves off the chronic diseases of aging, reducing the number of years of disability, dependency and pain.” (Reference 25.)

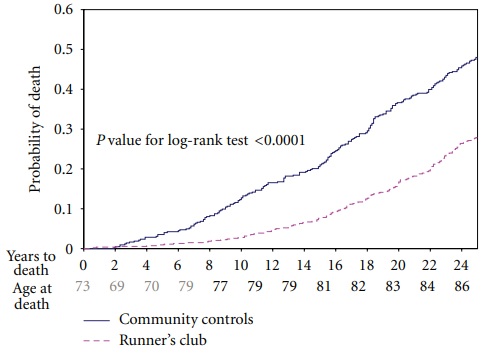

This study recruited 654 members (mean age 58.0) of a national running club for older runners and a community control group of 568 (mean age 60.7) Stanford University faculty and staff members who had an age, education, and socioeconomic status distribution that was very similar. (References 26 & 27.)

- The typical runners’ club member had run an average of 1,800 miles per year over the ten years before the start of the study. (The control group also had runners; these were not excluded because they wanted to have a sample representative of a community.)

- All subjects were asked to complete the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ-DI) every year.

- The HAQ-DI is described as “a self-reported instrument assessing functional ability in 8 areas: rising, dressing and grooming, hygiene, eating, walking, reach, grip, and routine physical activities… The HAQ-DI score is the mean scores of the 8 areas. It has been validated in numerous studies, is sensitive to change, and is widely used in observational studies and clinical trials.” (Cognitive problems are not specifically addressed but could certainly underly much of the measured disability in the study.)

- Figure 9 shows the average disability scores by age and calendar year for the study subjects who completed questionnaires through 2005 (21 years of follow-up). Over the years, the differences in disability between the runners and control cohorts grew steadily greater. The researchers estimated the similar levels of disability were postponed by more than 14 years in the runners, after adjusting for confounders.

- Dates of death through 2009 (25 years of follow-up) were obtained from the National Death Index (NDI).

- Figure 10 shows complete mortality data over these 25 years. The death rate among runners was 25% of the death rate for the controls over the first eight years. Subsequently, the two rates converged, so that at year 25 the runners had 60% the death rate of the controls.

- The NDI is a standard tool used in lots of studies. It contains information from the certificate of death, such as dates of birth and death and listed cause(s) of death and other significant conditions. There is a table in one of Standford Runners Study reports (results through 21 years) that categorize deaths by cause.

- The Runners group had significantly lower rates of death categorized as: coronary artery disease, stroke, cancer, and “neurological.”They did not report how many of the neurological deaths were attributed to dementia. Nor did they report how many of the total deaths had dementia listed as other conditions. (My mom’s death certificate, for example, indicates the immediate cause of death was “Respiratory Failure,” but does list dementia as first among “other significant conditions.”)

- I think it might be useful to extend follow-up for the complete study population at least to 2022 (38 years from study start, during which all but a small percentage have probably died) by using of all information in the NDI about cause of death and other significant conditions. Was being in the Runners cohort associated with a lower risk of dementia? If so, how much? Professor Fries died in 2021, but study data may be stored somewhere at Stanford. Querying the NDI would be easy and cheap.

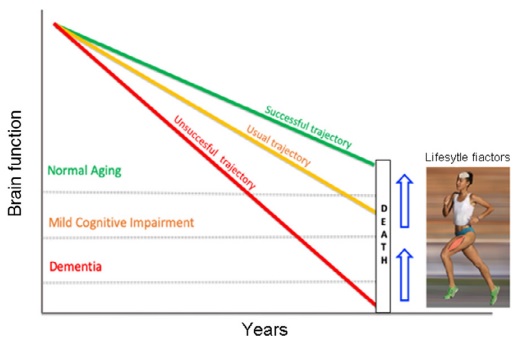

How PA May Protect Against Normal Cognitive Aging, MCI, and Dementia

It is very common for medical experts’ discussions of dementia to make the statement, “What’s good for the heart is good for the brain” and mention some of the risk factors for dementia that are also heart disease risk factors (such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, obesity) then briefly mention strategies to add a small amount of exercise to one’s day (“you don’t need to run a marathon” is another favorite line). It is rare to see vigorous PA called out as dramatically as in Figure 11. It is also rare to see much discussion of how PA may help with brain health (the biological mechanisms).

The best review I have found (so far) of potential mechanisms by which PA helps is Reference 29. This discusses:

- Protecting small blood vessels in brain from the high pressure of each beat of the heart (systolic pressure) by decreasing the stiffening of central arteries that occurs with age.

- The heart pumps blood to the brain through the first part of the aorta then the carotid arteries, which are large elastic arteries. “Increasing age is accompanied by a stiffening of the central arteries… [which] buffer the pulsatile output from the heart, reducing peak pressure, and providing a continuous flow to the smaller peripheral blood vessels. The brain and the kidneys are unique in their requirement for continual high flow perfusion throughout the cardiac cycle, and as such have lower resistance than other vascular beds. This leaves the microvascular structures within these organs much more vulnerable to increases in pulsatile energy than other tissues, which are protected by more robust upstream vasoconstriction. A recent review … concluded that the destructive effects of pulse pressure, which increases with age, is likely to be a significant contributor to the development of dementia.”“The degree to which progressively reduced elasticity in the central arteries can be considered ‘biological’ as opposed to ‘pathological’ is still a subject for debate and further investigation. However regular exercise appears to be one of the best methods for reducing the rate at which such decline occurs. During exercise the heart rate is increased; however, as a result of longer term exercise the heart rate remains lower at rest, thus reducing the overall number of cardiac cycles and the degree of pulsatile stress on these arteries. A broad range of research has found that, in middle-aged and older people, those who engaged in regular aerobic exercise had generally lower central arterial stiffness.”

- Runners (and others who regularly have vigorous aerobic exercise) tend to have a dramatically lower resting heart rate than age- and sex-matched people who do not. (I wear a Garmin watch that monitors my heart rate continuously. For years, my resting heart rate has usually been in the low 40s.) However, vigorous exercise causes a considerable increase in blood pressure during the exercise, so I wonder how much of the benefit of lower heart rate is offset by this.

- Improved cerebral blood flow (CBF) due to healthier endothelium in brain blood vessels. Better CBF results in better oxygen delivery to brain cells, which improves their functioning and survival.

- “Specifically, it is the capacity of the vascular endothelium [innermost cellular lining of all blood vessels] to produce and react to vasodilators, particularly NO [nitrous oxide], that declines most with increasing age; thereby reducing overall CBF as well as the capacity of the endothelium to respond efficiently to changing conditions and demands. Interestingly, general arterial function has been found to peak at around 30 years of age and then progressively decline, which directly parallels the age profile of cognitive decline.”

- “Recent meta-analytic analysis of 51 randomized controlled trials, primarily involving middle-aged or older participants, found that aerobic and resistance exercise, both individually and in combination, significantly improved endothelial function. Across these studies, higher intensity of aerobic exercise resulted in the most improvement, with a significant dose-response relationship… There are a number of proposed mechanisms for this exercise resilience to age-related endothelial dysfunction, including stimulation of the endothelial cells through temporarily increased shear stress and increased localized blood flow, increased levels of circulating catecholamines during exercise and lower resting heart rate reducing mechanical stress.”

- Increased production of various proteins (such as BDNF) that promote production of new neurons and synapses (connections between neurons).

- “BDNF [brain-derived neurotrophic factor] has emerged as a key mediator of cognition as it is highly expressed in regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus and cortex, that exhibit the greatest degree of plasticity.”

- “While the brain produces the majority of resting state BDNF levels, a study of younger adult males found that there was a 200 to 300% increase in circulating BDNF levels during aerobic exercise [other articles say this is produced by muscles], with an equivalent increase in the amount produced by the brain. However, this percentage contribution did decrease following 1 hour of recovery. As a corollary to these finding, a review of previous studies concluded that peripheral BDNF may actually be transported back to, and used in, the brain after exercise.”

- Reduced stress, reduced inflammation, and favorable hormonal effects. (I found the evidence hard to follow in these parts of the paper).

I am intrigued by the idea that PA can “buff up the brain as well as the body” to increase brain “reserve” and resilience to declines associated with normal aging or pathologic changes.

- The concept of “cognitive reserve (CR)” was developed to explain the epidemiological finding that higher education and/or more enriched life experience is associated with a lower prevalence of dementia. “You can think of cognitive reserve as your brain’s ability to improvise and find alternate ways of getting a job done. It reflects how agile your brain is in pulling in skills and capacities to solve problems and cope with challenges… [R]esearch has shown that people with greater cognitive reserve are better able to stave off symptoms of degenerative brain changes associated with dementia or other brain diseases…” (Reference 30.)

- PA-induced increases in BDNF may increase brain reserve by stimulating development of new neurons and more synapses between neurons. Better brain vascular health due to the beneficial effects of PA may also result in relatively more brain reserve.

- Figure 12 describes how different levels of brain reserve may explain why many individuals with neuropathologic changes of AD appear cognitively normal while others with similar changes meet criteria for AD. (Reference 31). Building higher reserve could slow the rate of development of dementia.

Figure 13 describes sequential stages of pathological brain changes in AD and the associated clinical changes. Initial memory loss is associated with atrophy of the hippocampus – the same brain region affected positively by BDNF.

I would Love to See Results of a Study of Endurance Running & Brain Health

It is possible that most of the brain health (and other health benefits) caused by increasing PA require only a small increase from “inactivity” or that, at best, increasing PA beyond a rather low level has rapidly diminishing returns or even that it results in worse brain health. Alternatively, chronically higher vigorous PA (the sort that produces marked improvement in cardiorespiratory fitness) may cause even greater brain health benefits. It would be helpful to investigate this by comparing the outcomes of small or modest levels of PA with the sort of PA typical of endurance runners.

My pie in the sky idea is to get a bunch of organizations and very smart people together to design, fund, and administer a longitudinal study of older runners, in order to better increase understanding of the brain health effects of higher levels of chronic PA than have been studied with samples intended to be representative of the whole population (which typically contain an insufficient number of long-term older runners because older runners are relatively rare).

- My initial thought is that runners might be recruited from regional marathons to participate in a study with long follow-up and opportunities to participate in exercise testing, neuropsychological testing, brain imaging, and/or who knows what. (Figure 14 shows a recruitment flyer idea that might need to be tweaked by a skilled marketing professional!)

- The control group might be non-running siblings and spouses of runners.

- I think a prospective study of even the most basic descriptions of older runners’ behaviors and health outcomes over time would be darn interesting. Interesting sub-studies could be designed, such as following running injuries and other factors that are barriers to continued running.

References

All the references I cite were obtained for free online (except for #15, Matthew Walker’s sleep book, I borrowed that from a public library). If you are interested in any of the ones without a hyperlink provided, I recommend entering the title of the article in a search engine like Google then looking through the results for those that require no payment.

- The Social Security Administration (SSA) life tables are available at: https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html.

- Life Expectancy in the U.S. Dropped for the Second Year in a Row in 2021 (cdc.gov).

- American Academy of Actuaries and Society of Actuaries, Actuaries Longevity Illustrator at: https://www.longevityillustrator.org/.

- https://www.johnhancock.com/life-insurance/life-expectancy-calculator.html.

- Wolters F, et al. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States: The Alzheimer Cohorts Consortium. Neurology (2020), 95(5): E519.

- https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/.

- Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostic Guidelines | National Institute on Aging (nih.gov)

- Hale J, et al. Cognitive impairment in the U.S.: Lifetime risk, age at onset, and years impaired. SSM – Population Health (2020), 11.

- Healthy Aging | Memory and Aging Center (ucsf.edu) .

- Salthouse T. Selective review of cognitive aging. J International Neuropsychological Society (2010), 16(5):754.

- Livingston G, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet (2020), 396:413.

- Morris M, et al. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimer’s and Dementia (2015), 11(9):1015.

- Mediterranean and MIND diets reduced signs of Alzheimer’s in brain tissue, study finds – CNN (March 11, 2023) (This article has a link to the scientific report. Unfortunately, the report is not available for free.)

- Winer J, et al. Sleep disturbance forecasts β-amyloid accumulation across subsequent years. Current Biology (2020), 30(21):4291.

- Walker M. Why We Sleep: Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams. Scribner Book Company (2018).

- Alzheimer’s Disease | What Time Hides for AD (timehidesalz.com) .

- https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/lecanemab-leqembi-new-alzheimers-drug .

- https://www.23andme.com/topics/health-predispositions/late-onset-alzheimers/

- Beckett M, et al. A meta-analysis of prospective studies on the role of physical activity and the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease in older adults. BMC Geriatrics (2015), 15:1.

- Sofi F, et al. Physical activity and risk of cognitive decline: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Journal of Internal Medicine (2011), 269(1):107.

- Tan Z, et al. Physical activity, brain volume, and dementia risk: The Framingham study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, (2017), 72(6):789.

- Palta P, et al. Leisure-time physical activity sustained since midlife and preservation of cognitive function: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Alzheimer’s and Dementia (2019),15(2):27.

- Defina L, et al. The association between midlife cardiorespiratory fitness levels and later-life dementia: A cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine (2013),158(3):162.

- Dementia: Physical fitness linked to lower risk of dementia | New Scientist (March 3, 2022).

- Stanford Medicine professor James Fries, proponent of healthy aging, dies at 83 | News Center | Stanford Medicine

- Chakravarty E, et al. Reduced disability and mortality among aging runners: A 21-year longitudinal study. Archives of Internal Medicine (2008), 168(15):1638.

- Fries J. The theory and practice of active aging. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research (2012).

- De la Rose A, et al. Physical exercise in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s. J Sport and Health Science (2020), 9(5):394.

- Kennedy G, et al. How does exercise reduce the rate of age-associated cognitive decline? A review of potential mechanisms. J Alzheimer’s Disease (2016), 55(1):1.

- What is cognitive reserve? – Harvard Health

- Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurology (2012), 11(11):1006.

- Kok F, et al. Potential mechanisms underlying resistance to dementia in non-demented individuals with Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology. J Alzheimer’s Disease (2022), 87(1):51.

Leave a reply to cjfielding2013 Cancel reply